‘Woodman, oh woodman, you must spare that tree,’ sings the folk musician Robin Grey on his album From the Ground Up (2017). ‘Touch not a single bough, for in my youth it sheltered me.’

The song is an old one. The words were written in 1830 by the American poet George Pope Morris, originally under the title ‘The Oak’, and set to music by the English pianist Henry Russell seven years later. It became a hugely popular drawing-room ballad, under its new title ‘Woodman, Spare That Tree’, and represents an early example – or perhaps a foreshadowing – of the environmental protest song. As such, it fits comfortably on Grey’s album, an environmentally minded collection from a songwriter who positions himself squarely in the radical protest tradition: From the Ground Up also includes lyrics about fossil fuels (‘leave it in the ground/I want our world to avoid being drowned’) and living off the land (‘I’ll be good to the land and the land will be good to me’).

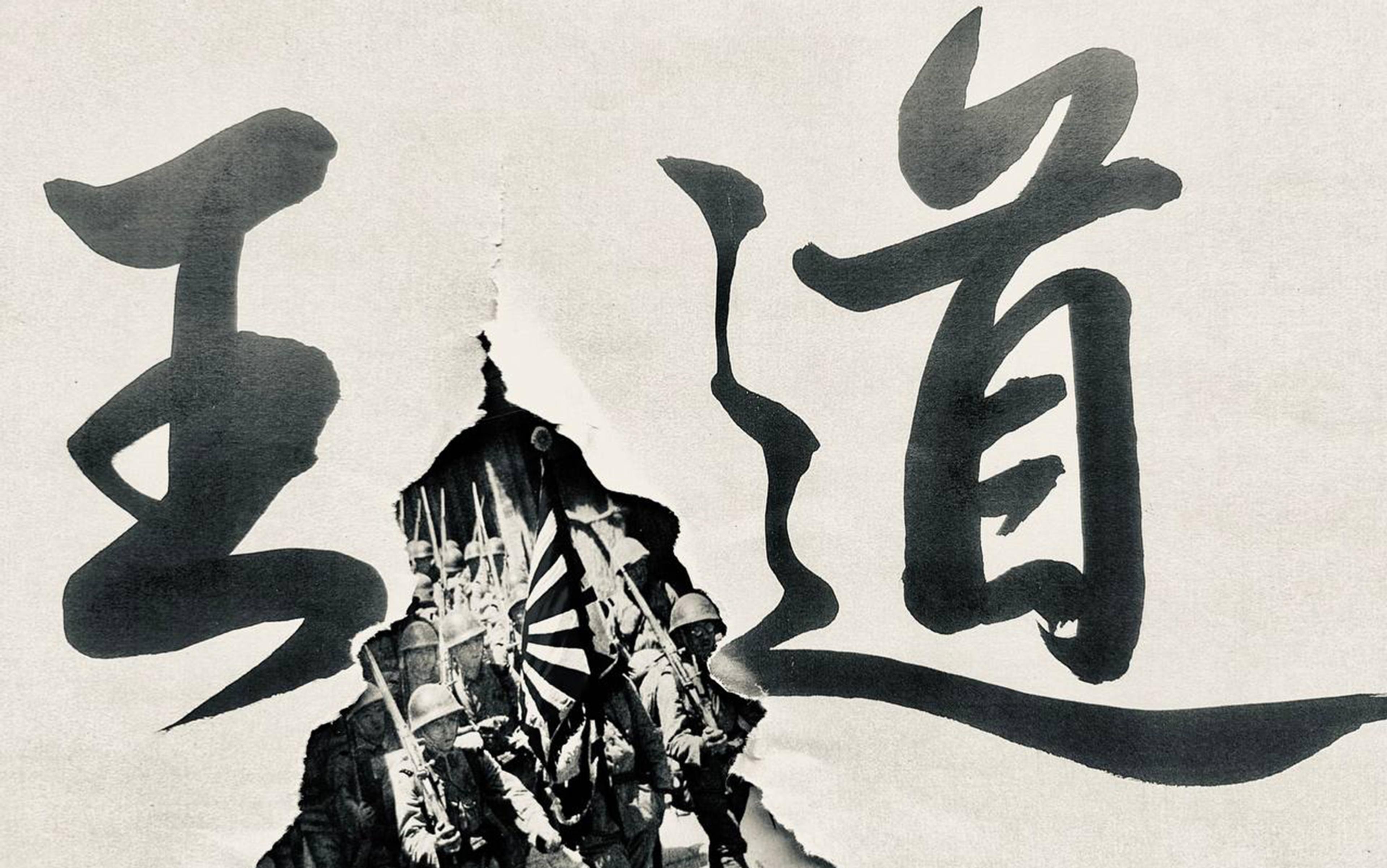

Grey works in the folk milieu that sometimes attracts the label ‘eco-folk’, an earnest, acoustic sub-genre of protest and folksong, festivals and woodcuts; it might seem derisive or satirical to say that it’s all bare feet and nettle soup, but both are encouraged at gigs by Sam Lee, one of the leading lights of the eco-folk movement. In recent years, the writer and academic Robert Macfarlane has helped to raise the profile of eco-folk with his plaintive lyrics for musicians including Karine Polwart, Julie Fowlis and Seckou Keita. His protest work ‘Heartwood’ – ‘Would you hew me/to the heartwood, cutter?/Would you leave me open-hearted?’ – is an obvious successor to ‘Woodman, Spare That Tree’.

Robert Macfarlane’s ‘Heartwood’ poem made into a linocut poster by Nick Hayes

This kind of environmentally conscious folk music builds on decades of enduring protest songwriting from postwar musicians such as Malvina Reynolds (‘What Have They Done to the Rain?’), Pete Seeger (God Bless the Grass) and Peter La Farge (‘As Long as the Grass Shall Grow’). In the present day, the enfolkification of rural protest – where demonstrations over climate change and land access are accompanied by folklore theatre and the music of fiddles and ukuleles – reinforces the popular image of folk as ‘green’ music. Protest music is, by its nature, uncompromising and one-eyed; no great protest song ever followed the middle eight with a verse beginning ‘But on the other hand…’ But successful art – like good history – engages with complexity and contradiction, and if the bright-green postwar trim is all we see of the relationship between folk music and the environment, we’re liable to overlook the significant fact that the voice of the folksong has as often been the voice of the cutter as it has the voice of the tree – just as it has more often spoken for the hunter than the hunted, and for the fisherman more often than the ocean.

Folk songs are workers’ songs, and if you look at human history our work has been to chop, dig, scour, subjugate, hunt, harness, seize and plunder. It’s the work of innumerable human hands and, as we’ve gone about this work, in the woods, in the hills, on the open sea, folk music has been our soundtrack.

Writing in 2021, at the height of the TikTok ‘Wellerman’ craze, the literary scholar David Farrier sought to flag up what he called ‘the dark side of the sea shanty’. ‘No one wants to be a killjoy,’ Farrier wrote in Prospect magazine, ‘but it’s worth recalling that the propulsive rhythms of these songs … measured the beat of organised plunder.’

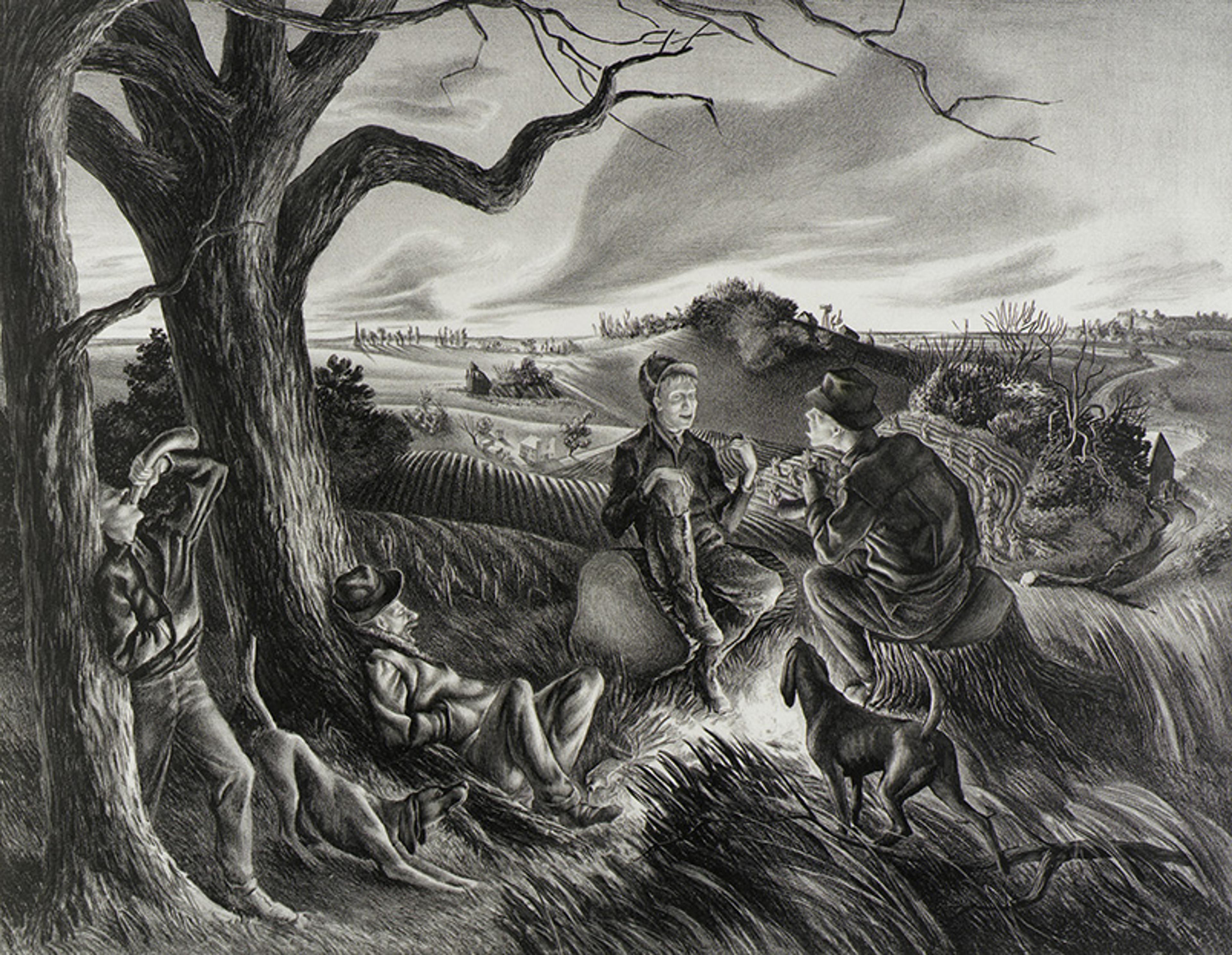

Folksong gives a human voice to centuries of environmental despoliation

‘Wellerman’ – a whaling song from the South Seas that propelled part-time Scottish folksinger Nathan Evans to worldwide fame – is a ‘cutting-in’ song, meant to accompany the rhythmic and bloody butchery of a captured whale. Farrier rightly observed that whaling was a murderous and monstrously harmful trade: the Otago whaling station, where in 1831 the Weller brothers founded the maritime provisions business that gave ‘Wellerman’ its title, could take in as many as 100 whales a year, and, as an ‘inland’ station, disproportionately targeted pregnant females and calves. This is in a sense a ‘dark side’, but it’s one that has always been in plain sight: these are above all human songs, songs of the Anthropocene, and so, as we’ll see, they have for most of their history been songs of human labour, human joy, human suffering, human love. In vanishingly few historic folksongs does the singer pity the whale or the fox. The woodman does not spare the tree.

For me, more than anything, folksong gives a human voice to centuries of environmental despoliation – and it reminds me, for all that the demands of capital, industry and technology turned our planet into a production line, a consumerist conveyor belt, that this was a human process: the stark sum total of centuries of lived experience among men, women and children. The values and priorities of historic folksong might not be our values and priorities, but they are foundational to our story.

The first piece of recorded music I remember hearing was a hunting song: ‘We’ll hunt him down, we’ll hunt him down,/We’ll run old Reynard to the ground.’ I must have been four or five, and my dad had it on an LP, or maybe on a cassette tape recorded from the radio. I’ve known that refrain as long as I’ve known anything. It belongs to a song called ‘The Hunt’, written and recorded in the early 1980s by the New Zealand folk singer Paul Metsers. The thing about it is that it is a protest song, an antihunting song – but it’s a hunting song, too.

In a handful of verses, performed a capella, Metsers deftly skewers the class privilege (‘I am the lord of all around/and me you shall obey’) and bald cowardice of the fox hunt (‘For sport it surely be/To hunt a single red fox down/With twenty men and three’). It’s the give-’em-enough-rope satirical form. Nothing much here is exaggerated or overblown, and there’s a great deal of beauty in the song too – more beauty, you might say, than the song really needs. There’s no mistaking the songwriter’s visceral dislike of hunting, but at the same time, in terms of the song and its traditions, it feels as though Metsers has gone native. Indeed, a whole verse seems to have no satirical content whatever: instead, Metsers tells us of the ‘silver air’, the huntsman’s horn, the barking of the hounds… one can quite readily imagine a hunter of the early 19th century listening in, but not listening too closely, and thinking: ‘Yes, yes, this is the stuff,’ even as he pulls on his red coat and saddles his hunter.

The English hunting song is above all else a pastoral, and praise for the fine, clear morning is fundamental to the form: ‘What a fine hunting day, it’s as balmy as May,’ ‘The morn is a fine one, right healthy and clear,’ ‘Tis a beautiful, glittering, golden-ey’d morn,’ and so on. In the end, ‘The Hunt’ shifts from satire to lament: ‘The air is still, and nature seems/To mourn another son.’ It’s a song that fascinates me because it operates – and succeeds – in both the protest and the pastoral traditions.

This relationship coexists with the remorseless daily practice of hunting, killing and consuming wild animals

Fox-hunters’ songs, of course, are not really work songs and in fact are barely folksongs in the traditional sense; however much hard physical work goes into maintaining a hunt, most such songs were sociable confections of the rural gentry, written in the 18th or 19th centuries, and are shot through with provincial allusions, sporting banter, jovial mythmaking about this or that celebrated hound, horse or huntsman. But even the most horny-handed old folksong didn’t spring from the soil by itself – there is always craft, always the consciousness of creation. Fox-hunting songs are by any definition songs of the people and of the land. And they have a place in a long, global tradition of songs of the hunt.

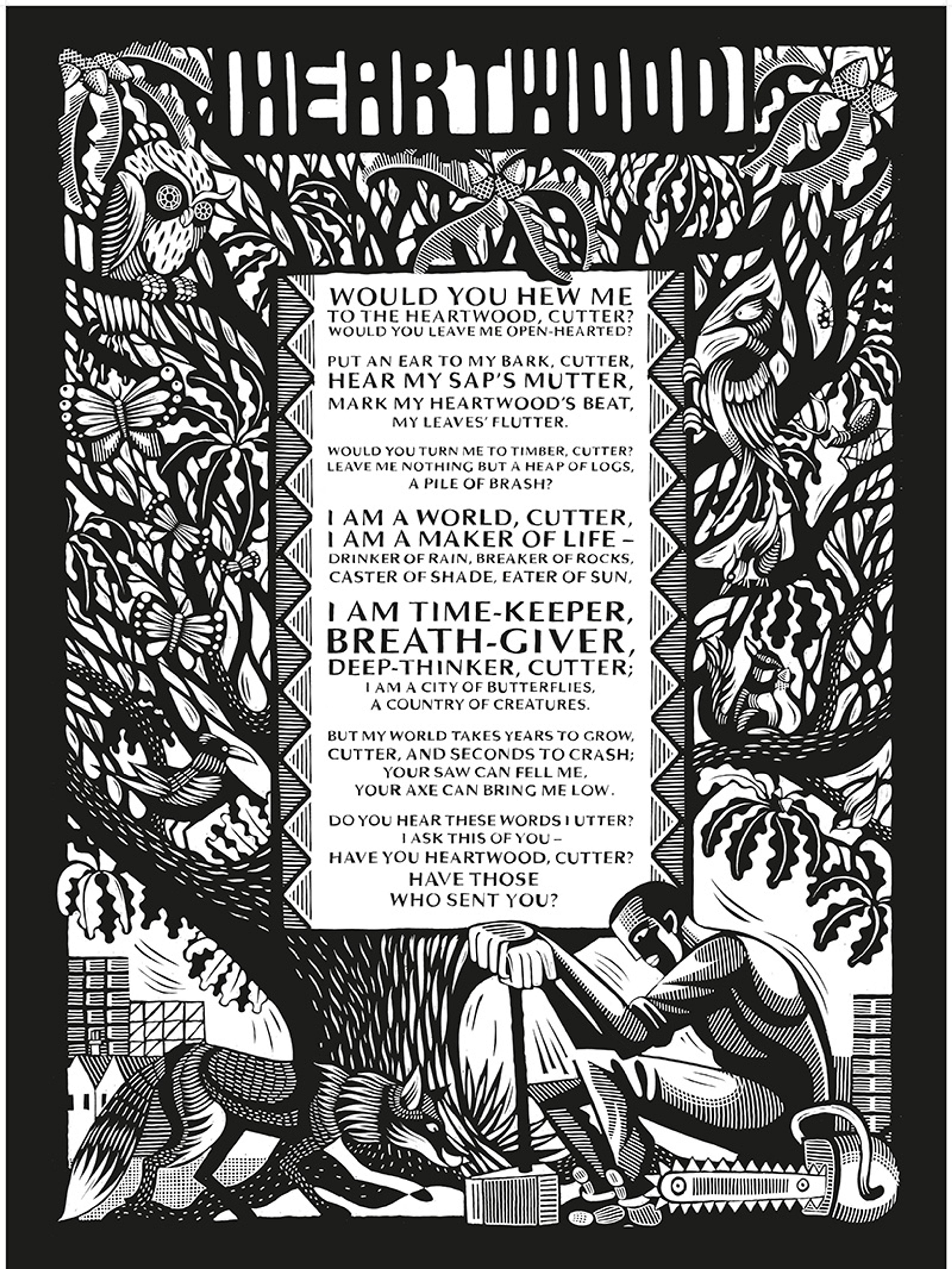

Blue Valley Fox Hunt (1938) by John Stockton de Martelly. Courtesy the Smithsonian Institution

The Canadian ethnomusicologist Lynn Whidden collected more than 80 traditional Cree hunting songs – niitooh-nikamon – in Manitoba and northern Quebec between 1970 and 2000. ‘The songs predicted successful outcomes for an occupation that is challenging and exciting in the extreme,’ she wrote in Essential Song: Three Decades of Northern Cree Music (2007). ‘The vivid images in the songs show the hunter’s appreciation of the animals and all of nature.’ So these, too, are pastorals – and they are work songs, in the most essential sense, because as Whidden writes, ‘The performance of a song stimulated the intuition and the creative power needed to capture a wild animal.’

‘The hunting songs,’ she adds, ‘are a personal expression of emotion, yet not one of the 86 that I recorded expressed sadness or regret.’ The Cree relationship with nature has been characterised as a covenant, as ‘spiritual agreements of reciprocity’ between the Cree and the nonhuman world. This relationship coexists with – indeed, is inseparable from – the remorseless daily practice of hunting, killing and consuming wild animals.

Many traditional songs of hunting have in common a fundamental complacency. This complacency isn’t to do with the nature of the hunting life – on the contrary, I think hunting cultures can only really exist by maintaining a cold-eyed view of how brutally generative and evolutionary processes operate on individual animals (‘So careless of the single life,’ as Alfred, Lord Tennyson put it). Rather, these songs express an implicit unconcern with the extent of the world’s natural resources. They aren’t the songs of a dwindling ecosystem (or rather, they are, but they don’t know they are); they’re the songs of eternal harvest, of a planet that renews itself, that seems intrinsically and forever bountiful. The reaping of the earth is an unending labour. What always was will always be. No doubt the 14th-century Polynesian settlers of New Zealand had their own joyous songs of hunting the moa, right up until the moas’ calls fell silent, and all the moas were gone.

This complacency of plenty facilitates a close focus on the human, on the hard lives and small comforts of the workers, rather than on the living world through which these men so destructively move. Songs of the whaling fleets, for instance, often dwell on the inhumanity of the industry toward the whaling crews – ‘They’ll use you, they will rob you, worse than any slave/Before you go a-whaling, boys, you’d best be in your graves’ runs a lament recorded in 1856. They also dwell on the rewards to be claimed, god willing, once the crew is back on dry land (‘And we’ll make our courtships flourish, boys, when we arrive on shore/And when our money is all gone, we’ll plough the seas for more’ is a fairly typical example, from 1832), but they very seldom consider the cruelty of whale slaughter: the ‘battles’ described are often violent and bloody, and the whales occasionally ‘gallant’, but they are there, when all’s said and done, to be harpooned, killed and tongued.

Early glimmers of eco-awareness are transliterated into worries about where the next paycheque will come from

This was a perspective that lived on well into the postwar protest age. The songs of the Scottish-Australian whaler and folksinger Harry Robertson, for example, tell of a rough life aboard whaling ships, of camaraderie and adventure. Robertson is not entirely indifferent to the cruelty of the trade, ‘of slaughter and of killing just to get that smelly oil’, but his is above all a hunter’s philosophy: ‘Where Nature’s largest creatures die and on factory decks they bleed,/Ordained by law of Nature, that man must meet his need.’ Robertson was active and popular throughout the 1960s and ’70s, even as conservation groups began to rally around the slogan ‘Save the Whales’ and Australia, in particular, moved towards an anti-whaling stance. Robertson’s songs ‘The Humpback Whale’ and ‘The Little Pot Stove’ – ‘Where the winter blizzards blow, and the whaling fleet’s at rest…’ – were even recorded as late as 1980 by the great British folk-revival musician Nic Jones.

An interesting feature of whaling folksong is the way in which early glimmers of a sort of eco-awareness – an awakening consciousness that Earth’s resources may not be infinite, after all – are transliterated into expressions of economic anxiety, gloomy business forecasts, and worries about where the next paycheque will come from. It’s thought that, before commercial whaling took hold in the northern oceans, there were between 9,000 and 21,000 North Atlantic right whales (so called because their habit of swimming near the surface and the shore, and their prodigious quantities of blubber and baleen, made them the ‘right’ whales to hunt). Many thousands were taken by Basque and New England whaling ships in the 16th and 17th centuries; by the turn of the 20th century, decades of industrialised hunting and slaughter had left the population close to zero.

Attacking the Right Whale (c1835) by Ambroise Louis Garneray. Courtesy the Peabody Essex Museum; Salem, Massachusetts, United States/Wikipedia

‘If I had the wings of a gull, my boys,’ sings the narrator of ‘The Weary Whaling Grounds’, a song of the mid-1800s, ‘I would spread ’em and fly home./I’d leave old Greenland’s icy grounds/For of right whales there is none.’ What he described was known in the fleet as ‘whalesickness’, not, as we might imagine, a disorder associated with prolonged exposure to slaughter and butchery (something like Dashiell Hammett’s description of a villain going ‘blood simple’) but really quite the opposite: a pervasive melancholy brought about by a poor whale catch – the name draws a comparison with ‘homesickness’. The kicker in the song, ultimately, is financial: ‘But we go to the agent to settle for the trip,/And we’ve find we’ve cause to repent./For we’ve slaved away four years of our life/And earned about three pound ten.’

The near-extinction of a species, here, is cast not as a tragedy but as a commercial downturn, perhaps a business misjudgment, similar in character to a crash on Wall Street, but in any case another kick in the teeth for the hard-pressed working man. In the 20th century, Robertson voiced a similar sentiment: ‘Not a whale caught today,/Bloody Jonah’s had his way.’ From this angle, ‘Save the Whales’ is not so much a plea for mercy as a business proposition.

When it comes to logging, another hugely profitable North Atlantic trade, there was no parallel ‘treesickness’, and greater grounds for a measure of complacency. The foresters of the vast Canadian woods sang, like whalers and sailors, of hardship, labour and camaraderie, but the woods seemed literally endless: we know now that they cover some 2.4 million sq km, an area around 18 times the size of England. In her novel Barkskins (2016), Annie Proulx dramatises the lives of early 18th-century foresters. ‘What resource existed in this new world that was limitless, that had value, that could build a fortune?’ wonders a prospective timber merchant. Proulx goes on: ‘He rejected living creatures such as beavers, fish, seals, game or birds, all subject to sudden disappearance and fickle markets … There was one everlasting commodity that Europe lacked: the forest.’

In the 18th and 19th centuries, there was an unchecked expansion in logging across the northeast woods of Canada, and the emergence of lumber-camp or ‘shanty’ culture among the men who undertook this tough seasonal work. Shanty folksong – like most folksong, in most places – played multiple parts in the lumbermen’s lives, serving variously to memorialise the lost (logging was dangerous work), to voice grudges (the satires of the songwriter Larry Gorman were notoriously vituperative about both his peers and his employers) and, of course, to entertain.

No one in the camps sang laments for the fallen pines, hemlocks, cedars, white oaks or birches. To fell a tree was not a tragedy and still less a crime; it may even have been an accomplishment – ‘For spectators they will thunder,/They’ll gaze on you and wonder,/How noisy was the thunder,/The falling of the pine,’ as one of the oldest North American lumber songs has it. But, above all, felling trees was simply the work, the job to be done, the living to be made.

This was a working culture where nature was hostile and men were replaceable

‘Peter Emberley’, a ballad from northern New Brunswick, was written in the 1880s in response to the death of a young woodsman from Prince Edward Island: ‘I hired for to work in the lumber woods,/Where they cut the tall spruce down,/It was loading two sleds from a yard/I received my deathly wound.’ Another old song, ‘Harry Dunn’, or ‘The Hanging Limb’, tells of a man whose death in the woods – ‘a hanging limb fell down on him and sealed his fateful doom’ – causes his mother and father to die of grief. ‘The Jam on Gerry’s Rocks’, perhaps the most famous of North American lumber songs, commemorates the death of six men and their foreman, Monroe, in a logjam: ‘Meanwhile their mangled bodies a-floating down did go,/While dead and bleeding at the bank lay that of young Monroe.’

These songs are extraordinary memorials, stark, candid and enduring acts of not-forgetting in a working culture where nature was hostile and men were replaceable. They are often artless and sentimental. They are also statements of acknowledgement and witness. Human pain and human grief may seem to shrink to almost nothing in the great shadow of the eternal woods but these songs insist, stubbornly, that they are not nothing, they are not footnotes, they are not subsidiary losses, collateral damage – on the contrary, they may be, in the deep, cold, unfeeling forest, the only thing worth singing about.

It’s important to remember that these are not drawing-room ballads of far-off adventure and distant glory. They are the songs of the shantyboys themselves. These men knew when they sang these songs that what happened to Harry Dunn, what happened at Gerry’s Rocks could just as well happen to them, today, tomorrow, who knew? ‘Few shantyboys had not seen one of their friends killed,’ wrote the great Canadian folklorist and song collector Edith Fowke in 1961, ‘and they all took a very personal interest in the details of any accident. On the long winter nights when they sat around in the shanties, the songs that were called for most frequently told how some unfortunate shantyboy had met his fate.’

‘Have you heartwood, cutter?’ pleads Macfarlane, speaking for the trees, in ‘Heartwood’. It’s true, of course, that the logger doesn’t weep for the tree, nor the whaler for the whale, and that, partly in consequence of this, our world is less rich, less full, more deeply scarred. But it would be a mistake to conclude from this that loggers and whalermen – for they were of course mostly men – weren’t men of heart and sentiment (and indeed sentimentality). The songs of workers, even where the work seems to us blundering, cruel and wasteful, embody their own complicated human values, to do with family, love, work, fear, friendship, home, joy, justice, pain, courage, reward – it would be a mistake to dismiss these things as shortsightedness or anthropocentrism.

Perhaps the ethos of the rural-industrial is stronger in North America than in Europe. Perhaps the scale of industrial operations in the US countryside – enabled, of course, by the vast scale of the landscape – makes it easier to think of a forest as a workplace, or a product, than to see it a living habitat. But even in places where the balance between life and labour is more subtle, we can find in folksong a sense of the pre-eminence of work. The land, ‘nature’, may be the ultimate wellspring of our sustenance and shelter, but it’s no good to us without the intervention of labour, without the work of intermediaries: the farmer, the hunter, the forester, the reedcutter. ‘Nature’ may be friend or foe; it’s work that determines which.

The powte is no conservationist. He speaks for the fen as a resource, as worked land

‘The Powte’s Complaint’ is a ballad of the early 17th century, collected in 1662 by the antiquarian William Dugdale. It’s a powerful and belligerent protest song, railing against the drainage of the Norfolk fens (a socially and ecologically unique wetland of low-lying eastern England, which from this period onward was steadily reclaimed for pasture) by wealthy landowners. Its narrator is a ‘powte’, thought to be a fish now known as a burbot, and the putatively nonhuman perspective has prompted some commentators to classify ‘The Powte’s Complaint’ as an early ecological song – proto-eco-folk, perhaps. The Shackleton Trio are among the folk artists to have recorded the song in recent years.

The Shackleton Trio’s ‘The Powte’s Complaint’

I would agree that ‘The Powte’s Complaint’ is indeed a protest song, and in some senses an environmental song. But who, exactly, is the bold powte speaking for? ‘Stilt-makers all and tanners, shall complain of this disaster,’ he says. ‘For they will make each muddy lake for Essex calves a pasture.’ The powte is no conservationist. Certainly, he speaks for the fen, but not for the fen as a nonhuman ecosystem; the powte speaks for the economy of the fen, for the fen as a resource, as worked land. ‘Whatever species [of fish] the author imagined as the persona, one might contend that the song’s primary concern is with the impact of the drainage on the human economy,’ write Todd A Borlik and Clare Egan in a 2018 analysis. ‘It laments that destroying wetlands will cripple the water-dependent trades of boat-makers, stilt-makers, fishermen, and tanners; the last of these, it should be noted, were notorious polluters. So it would be rash to attribute firm environmentalist motives to the author of the song.’

It’s worth pointing out that anthropocentrism lands differently when, as Borlik and Egan go on to note, ‘the distinction between economy and what we now call ecology [is] not entirely discrete’, when the countryside and the working life are obviously codependent, and a clear ‘us’ and ‘them’ binary hasn’t yet developed between the rural and the industrial – when the work is the land, and the land is the work. Of course, in reality, the codependence has always been there, whether we’ve noticed it or not. We perhaps sense it more acutely, in these late days of climate breakdown, than we have done in many decades.

In any case, there are always difficult paradoxes lurking in any question about our connection with, or closeness to, nature, and these inevitably rise to the surface when we listen to the folksongs of the countryside. There is a profound and important connection between the living world and the hunter or whaler or logger whose livelihood literally depends on that living world, on its resilience and persistence, even as he hacks away at it. This is the kind of connection that we find in so many of these songs. It might not be eco-folk – and it won’t save the world! – but these too, nonetheless, are the living songs of our turning Earth.

Folk music has always been the music of pressed men and women, conscripts, foot soldiers; or rather, these people have always sung songs, and the songs they sing have always shaped our folk music. The rich and valuable tradition of protest in folk, that is, the tradition of ‘the people’ against the system, the octopus, the machine, runs parallel to an equally rich heritage of voices from within the system: the songs of the workers whose struggles – to work, to earn, to feed families, to build hard lives in hard places – constitute a powerful narrative in their own right. This, no less than the narratives of extinction and ecocide, is a narrative of losses, hardships, and the tenuous endurance of hope.

We can identify the systemic causes of environmental decline and ecological collapse (unregulated capitalism, extractivist colonialism) without losing sight of the fact that, in practice, at the business end, these causes operated through people – people who, as a rule, were seldom in a position to look far beyond the enclosing pines or the bulwarks of their whaler, or farther ahead than the next payday, the end of the voyage, the return of fathers, brothers, sons from the hunt or the sea or the north woods. This is the lived experience that is preserved (pickled, salted, barrelled) in our folksongs.

Folk music is protean by its nature, but it can fairly be said to be, among much else, rural music, pastoral music – a music of farmland, woodland, shore, ocean, music of wild places. As long as, when we say that, we see how, as well as dirt under its fingernails, it has always had blood on its hands.