A few weeks before Trevor went missing, Annie disappeared. She left one day in February 2022. Thousands of people looked for her, but their hopes dwindled as time went on. After a week, a local ornithologist told a reporter that: ‘Given the amount of time she’s been missing, it’s probable that she’s gone.’ News spread quickly that Annie, the most famous falcon in California – maybe even North America – had likely been injured or killed.

Before she disappeared, more than 20,000 people from all over the world watched her every day through live cameras that ornithologists had placed near her nest on top of a tower at the University of California, Berkeley in 2019. She and her lifelong mate Grinnell first showed up in 2016 and soon become iconic images of wildness in an urban landscape. I started watching Annie during the COVID-19 pandemic, after hearing a colleague talk about her as though she was an old friend: ‘You’re not going to believe what Annie did today…’

Mostly, the cameras showed her perched on a ledge, her yellow-rimmed eyes searching the metropolis below. I watched, mesmerised by Annie’s vulnerability and strength – she was a promise of what might survive in the face of all we were losing. When I looked through the eyes of the cameras, I felt my own animal self staring at another on the opposite side of the screen. Sometimes, she seemed so close I felt I could put my face to her feathers.

Annie’s nest atop the tower at Berkeley was about 25 minutes from my house. When she went missing, I searched the sky for her pointed blue-grey wings, imagining them spreading nearly three feet through the sky, with dark brown bars making striped horizons across her white chest. But I saw only sky.

Three thousand miles away, just a few weeks after Annie disappeared from the falcon cameras, a different camera caught a 45-year-old man leaving his car in the parking lot of a beach in New York. It was 2:30 in the morning. The cameras showed him leaving his vehicle and walking toward the water, then faded to black. The next day, his family reported him missing. Trevor’s car was still in the parking lot, a few miles from where we both grew up.

I had known Annie for only a few years of my adult life, but I had known Trevor since I was 17 years old. We got to know each other at the end of 1993, right around the time the European Union was established and Toni Morrison won the Nobel Prize in Literature. And we grew closer the following year as we spent more and more time with each other – I remember watching the infamous police car chase of OJ Simpson from the couch in Trevor’s family room. That was also around the time when I read Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death (1969).

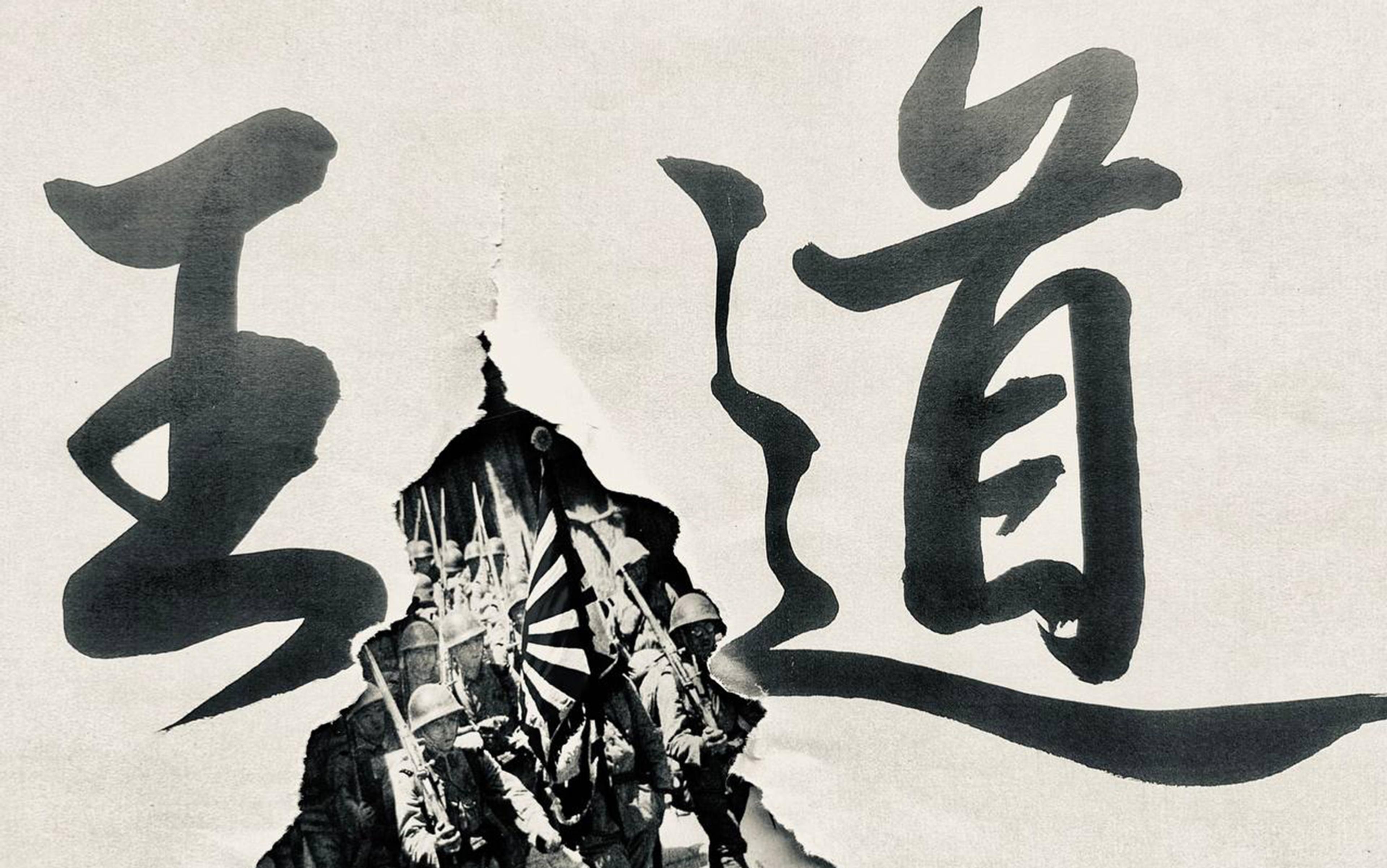

Emily and Trevor. Photo by Storm Choi

I couldn’t get Slaughterhouse-Five out of my head after Trevor and Annie went missing. When I first read it and learned about Vonnegut’s protagonist – a Second World War vet named Billy Pilgrim who becomes unstuck in time – my brain exploded. Over the course of the book, Billy returns to different moments in his life, including the war, and the period when he lived naked in a zoo on a planet called Tralfamadore, inhabited by aliens called Tralfamadorians. From these aliens, who live every moment over and over again, Billy learns that time is not linear. ‘The Tralfamadorians,’ he explains, ‘can look at all the different moments just that way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains … It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads on a string, and that once a moment is gone it is gone forever.’

After Trevor went missing, the ache to believe this was true was so surprising and sharp, I felt it in my chest. If we couldn’t find him in this present moment, could he still be somewhere else – maybe back when we were just kids, when everything was as fine as it would ever be? I let myself dream.

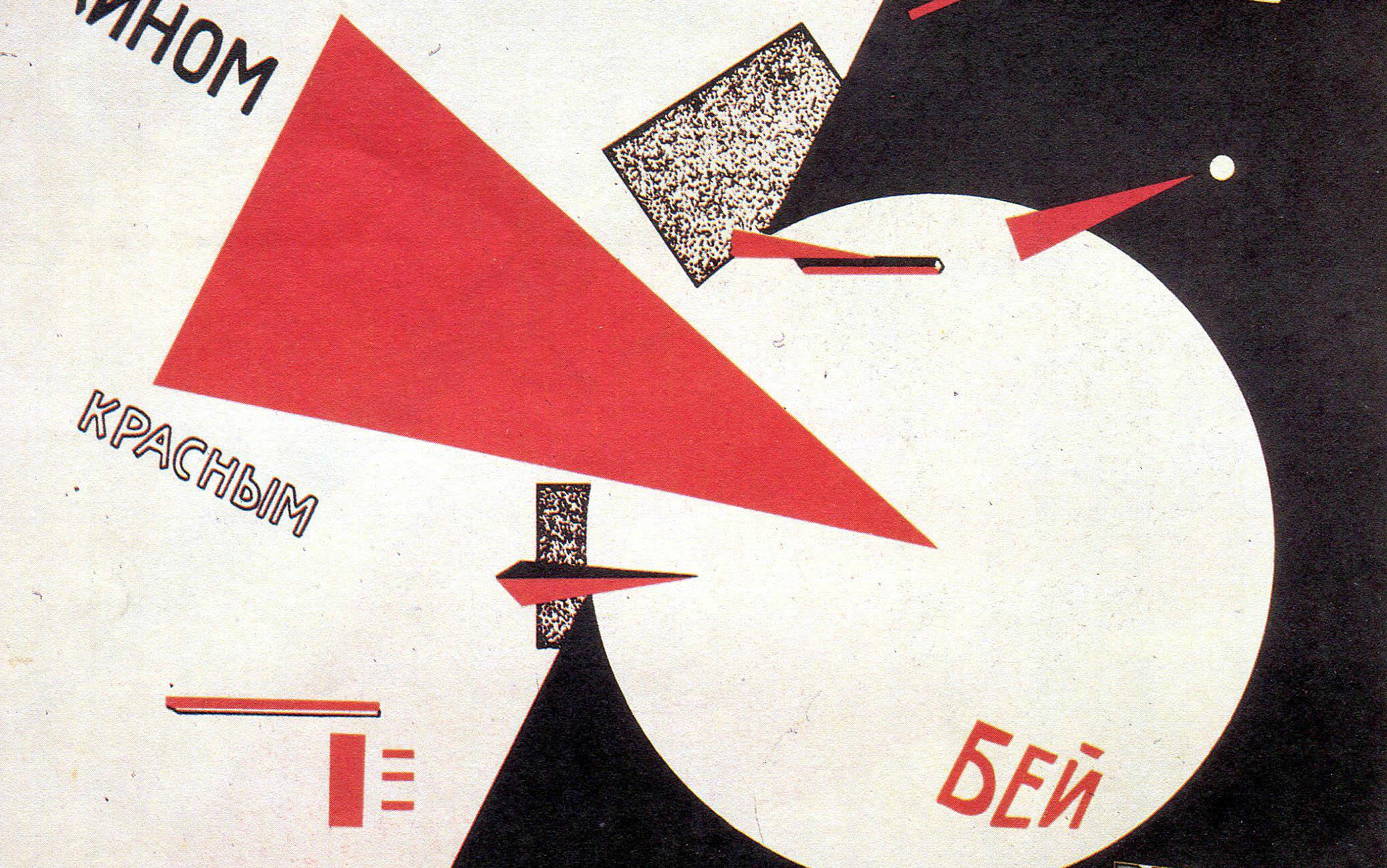

The phrase ‘So it goes’ is written 106 times across the 186 pages of the first edition

Slaughterhouse-Five is a story of time travel, but it is also a story about death. So many people die in Slaughterhouse-Five. Everywhere Billy goes, it seems somebody has died or is going to die. They die during battle. They die from illnesses. They die in plane crashes. His wife dies from carbon monoxide poisoning. Billy himself is murdered.

The largest number of deaths take place in Dresden in Germany where Vonnegut was also a prisoner of war, locked up like his protagonist Billy in a pig slaughterhouse. And, like Billy, Vonnegut also survived the firebombing in 1945, which destroyed the city and killed as many as 25,000 people.

‘So it goes.’

Every time there is a death in the book, the narrator repeats those three words. The phrase ‘So it goes’ is written 106 times across the 186 pages of the first edition. When Salman Rushdie wrote about this Vonnegutian mantra for The New Yorker on the book’s 50th anniversary in 2019, he claimed that most people who hear the phrase accept it as a resigned commentary on life:

Life rarely turns out in the way the living hope for, and ‘So it goes’ has become one of the ways in which we verbally shrug our shoulders and accept what life gives us.

But Rushdie doesn’t think that is what Vonnegut wanted to say: the phrase ‘is not a way of accepting life but, rather, of facing death.’ The irony of ‘So it goes’ is that it communicates the depths of grief, hidden within an acceptance of how things are. ‘Beneath the apparent resignation is a sadness for which there are no words,’ Rushdie wrote.

When I read Slaughterhouse-Five the first time, I bristled at how often ‘So it goes’ appeared on the pages. No death is immune to it. Billy says the phrase after the death of his wife, after ‘the greatest massacre in European history’, and after the potential end of the universe. It does not matter if death is merely part of the natural order of things or follows a brutal massacre. ‘So it goes’ is always waiting to punctuate the end of life. I wondered if the effect flattened the sharp and personal pain of grief into something so generic that it might desensitise us to it entirely. Vonnegut draws the same blanket over death’s many faces, no matter how near or far, big or small.

When I reread the novel again after Trevor disappeared, I no longer understood the phrase as a shrug or a resignation. Instead, I read those three words softly, with tenderness, as a mantra gesturing to the ways we have all been wounded by loss, even as we still fight to save who and what we love. I don’t believe ‘So it goes’ is only a way for us to ‘face death’. I think it is a way for us to face each other, to connect with the ones still alive – those left with the active work of grieving, which is to say, the active work of living. It is not a phrase we are meant to whisper alone to help us quietly accept the suffering of the world. It’s words that can connect us to each other, expressing the grief of being alive, together – expanding, not shrinking, this experience. It is both a contradiction and an invocation, communicating the indescribable sadness of living through loss, a ‘sadness for which there are no words’.

If ‘So it goes’ helps us to face each other through our shared suffering, then how did Vonnegut want us to face our dead? I think he offers us a way to do this by describing linear time as an illusion. By showing us that time doesn’t really follow a linear sequence, ‘like beads on a string’, he was imagining us freed (if only for a moment) from the constraints of grief. ‘When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse,’ Billy explains, ‘all he thinks is that the dead person is in a bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments.’ The possibility of time travel, of nonlinearity, lets us take a breath from the pain, by imagining a nonlinear escape, even if there was nothing we could do to stop the arrival of our suffering in real time.

I hadn’t seen Trevor in more than 15 years when Mike first called to tell me he was missing. Mike called from the beach as he was searching for him. He told me Trevor had not been well for months. He was not acting like himself.

Trevor and I became friends nearly 30 years ago when we were seniors in high school. We both chose to take a leadership class that culminated in student-led performances meant to educate our peers about sex. Having no experience either with sex or the education of others, I have no idea why I took this class. I was awkward in my one-piece jumpsuit that gave me the air of a car mechanic, with my frizzy brown hair held back by a heavy brass clip that looked like I stole a trumpet from the marching band and squashed it on my head. Though I could recite every love poem by Pablo Neruda in English and Spanish – ‘it grows and roams / within us,’ he writes in ‘Ode to Time’, one of my favourites, ‘it appears, / a bottomless well, / in our gaze, / at the corner / of your burnt-chestnut eyes / a filament, the course of / a diminutive river, / a shooting star / streaking toward your lips’ – I had never come close to having a boyfriend, or to believing I was somebody who could be loved. Trevor, however, was different. A star athlete and a popular straight-A student, he took pleasure in being a paternal figure to those closest to him. He was knowledgeable about everything and loved by everyone who met him.

When he kissed me, I thought I could never read another Neruda poem the same way again

I don’t remember how our conversations after class turned to conversations on the weekends. They weren’t really ‘conversations’, they were almost always arguments. No topic was too big or small or weird – we debated the reasons for Barry Manilow’s success; the benefits of sharing a birthday with a sibling (which he did and loved); the geopolitics of Russia and whether it was better to stay where we grew up or leave. (I was always going to leave, mistaking leaving for having a ‘big life’, and he was always going to stay, believing that he already had one.) The tension in our debates was playful but, through it, we were also staking a claim and mapping our identities – his, calm and rational; mine, starry-eyed.

Sometimes, though, we didn’t talk at all. We’d walk along the beach or park at an overlook facing a nearby powerplant and lay on the roof of his parents’ Jeep. Sometimes, I sat on his lap in the driver’s seat while he taught me how to drive down the hills that led into town. When he kissed me one night, I thought I could never read another Neruda poem the same way again.

Now, nearly 30 years later, Trevor’s car sat empty in a beach parking lot a few miles from that overlook. I sat in a chair and waited for him by my window just like I did when I was 17. When I finally fell asleep, I dreamed about a boy and a bird. In my dream they were together. They were safe.

Nameless birds appear at the beginning and the end of Slaughterhouse-Five. In the first chapter Billy says:

[T]here is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre … Everything is supposed to be very quiet after a massacre, and it always is, except for the birds. And what do the birds say? All there is to say about a massacre, things like ‘Poo-te-weet?’

This is how the novel ends, too. As the trees leaf out, the silence after death is broken only by a bird who asks Billy a question: ‘Poo-te-weet?’

According to the journalist Tom Roston, approximately 125,000 copies of Slaughterhouse-Five have been sold every year throughout the 21st century. I think so many of us watched Annie on the cameras for the same reasons we read Vonnegut’s novel. We wanted to see a pilgrim on their journey. We wanted to witness a living being surviving in the face of danger, relentless risk and constant precarity. We wanted to imagine a world where it was possible to endure and adapt, despite looming existential threats. We wanted to travel through time and space and even beyond the bounds of what we know to be true. We wanted to believe that anything was possible.

The history of the peregrine (pilgrim) falcon, Falco peregrinus, is another tale that might make you believe anything is possible. It is a story written with absences. As development spread across the United States at the turn of the 20th century, peregrine populations declined due to an unprecedented loss of habitat. And by the mid-1960s, peregrine falcons were extirpated from the eastern US while their numbers dramatically declined everywhere else. Around the world, use of the poison DDT (intended to control mosquitos and other insects) had caused eggshells to thin and weaken, making them unable to support the weight of incubating birds, which nearly wiped peregrines off the face of the Earth. The species was declared endangered in 1970. And by 1975, according to California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife, there were just over 300 known falcon pairs in the US. Then, in the decade after DDT was banned in 1972, falcons started to make a gradual comeback. And since the mid-1970s, more than 6,000 American peregrines have been bred in captivity and released.

For years, so many people had watched her, loved her. Now their grief was shared on social media

Today, even though peregrine falcons have been restored to their historic range, they still face threats. Before Annie went missing, she and her partner Grinnell lost children and battled falcons for their territory. And months before Annie’s disappearance, Grinnell was even found wounded and nearly dead, on top of a garbage can. But they survived.

I think this is part of the reason why thousands of people looked for Annie when she disappeared. A team of volunteers monitored the tower and, as people all over the world watched for her on the live cameras, ornithologists made guesses about what happened. She was likely injured while hunting, they said. She was trapped in a building. Maybe she went to visit falcon relatives on Alcatraz Island and got hurt.

After she was missing for a week, most presumed she was dead. The ornithologists who helped launch Cal Falcons, the group who first set up the falcon cameras, Tweeted that she may have died: ‘Unfortunately, we believe that Annie has either been displaced from the territory, is injured or dead.’ For years, so many people had watched her, loved her. Now their grief was shared publicly on social media. For the ornithologists, the hardest comments to read were from elementary school teachers who had to tell their young students the news. One member of Cal Falcons described the role of the team as something like a ‘biological grief counsellor’ for distraught falcon fans.

Then, nine days after Annie went missing, a scientist caught sight of a falcon sitting on the edge of Annie’s nest. She had calmly returned. Scientists were dumbfounded. ‘[T]his is something that is totally unexpected and goes against pretty much everything we’ve seen,’ the ornithologists who monitored her reported. It seemed impossible: a falcon returned from the dead to be with her mate.

Where did Annie travel to? And more importantly, what led her back? When Trevor went missing a few weeks later, I began asking the same questions. If I could just figure out how Annie got back, perhaps I could figure out the same for Trevor. As I reread Slaughterhouse-Five, I hoped things would finally come right, that Annie’s return might promise a reprieve from the inevitable. But hope can be so thin, barely able to hold the weight of life – and sometimes the inevitable isn’t what you imagined at all.

On the last day of March, nearly a month after Annie and Grinnell reunited, a pedestrian found Grinnell’s mangled body in the middle of a street in downtown Berkeley. The group who monitored the falcon family spoke for thousands of us all over the world: ‘We are devastated and heartbroken.’ Either he was in a fight, ornithologists suspected, or he got too close to the road and was struck by a car. His body was too destroyed for an autopsy.

In August 1994, on the last night before Trevor left for college, Mike invited friends to sleep over at his house for one final celebration. Since most of us would be leaving for college within the month, it was a chance to say goodbye. Trevor and I stayed up long after everybody went to sleep, talking softly. In my diary, I later wrote: ‘And I told him everything I needed to.’ I didn’t elaborate. What did my 17-year-old self need to say? That he was the best person I knew? That I was in awe of the way he took care of the people he loved? That I knew he would make a life in our tiny town, and I would leave and never come back?

On that last night we were together, I woke again and again to find him looking at me, tracing my face with his fingers, like a sailor trying to remember a map or a child memorising the lines to a book they loved. In the morning, we drove down to the harbour, sat in the parking lot overlooking the beach, and cried.

Trevor and I kept in touch as friends in college, connecting when we were home on school breaks and writing long letters to each other that eventually grew sparse as we stretched into adulthood. When he went missing, I searched his letters for clues that might foreshadow the sickness that would come later. But I found only good memories.

We returned to remember who we were when the world was young and we were just waking up to it

The last time I saw him in person was during the summer of 2004. We spent a weekend together with friends at a small beachside cottage for Mike’s wedding. I was almost 30 and living in a shared apartment in Harlem. Trevor was a cardiologist now, on his way to getting five board certifications. He was engaged to a woman he loved. I was three years into a loving relationship with an acupuncturist I’d marry a few years later. Trevor and I had grown into comfortable buddies in the years since high school, and easily slipped back into the familiar banter of old friends who grew up together.

That summer, on the night before the wedding, Trevor, Mike and I returned to our young selves as if we were always tethered there. We returned for just a night, to remember who we were when the world was young and we were just waking up to it. The three of us stayed up talking and laughing until the orange lid of the sun crested over the bay. I later wrote in my journal: ‘Everybody should know what it is to have friends like these. Everybody should know what it is to be loved like this.’

A week after Grinnell’s body was recovered from a busy street in Berkeley, Trevor’s body was found in the water not far from where he was last seen. I wanted to attend the funeral, but with young children to take care of, it was impossible. Friends said there was a line all the way around the block. You couldn’t see where it ended.

After Grinnell died, hundreds of mourners left flowers, notes and photos at the foot of the falcon’s bell tower. But only one day later, another falcon was spotted in Annie’s nest. Ornithologists named him ‘New Guy’. We all watched as New Guy defended the nest from other birds, sat on the eggs, and even brought a large mourning dove to share with Annie. She was seen copulating with him before laying another egg. How could she move on so quickly, mourners wondered, if her bonds with Grinnell were so strong? Don’t falcons mate for life? Annie had been with Grinnell for many years, but the raptor expert who retrieved Grinnell’s body said her acceptance of the new falcon was no surprise. ‘She only has two imperatives: survival and reproduction. This isn’t a bad thing.’

Grief, as humans understand it, does not seem to be an imperative for peregrine falcons. I started to wonder what we might have to learn from Annie. What did her version of ‘So it goes’ look like? I wondered if she was mourning in her own falcon way, with a different sense of time and permanence, a sense more like that of a Tralfamadorian who could, as Vonnegut wrote, ‘look at all the different moments just that way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains … It is just an illusion …’

Did she wonder, like I did, that someone she was close to might now be somewhere else, in another moment, maybe back when we were younger, when everything was as fine as it would ever be? Did she dream, too? No one knows.

Vonnegut wasn’t only trying to show us the nonlinearity of time and the horrors of war

I have long debates with Trevor about what Annie was thinking, mostly when I’m driving to work – entire arguments in my mind. I hear his laugh so vividly, I’m certain he’s in the car with me. But these debates are not a product of time travel. It is just somebody feeling grateful for an old friend and doing her best to remember him.

I think Vonnegut, who died in 2007 aged 84, wasn’t only trying to show us the nonlinearity of time and the horrors of war when he wrote Slaughterhouse Five. By offering us a portrait of personal and universal grief, and the way that loss permeates our lives, he was pointing toward something else. Steve Almond captures this in his tribute to Vonnegut, an essay titled ‘Everything Was Beautiful and Nothing Hurt’ (2009):

Vonnegut has been trying to explain [something] to the rest of us for most of his life. And that is this: Despair is a form of hope. It is an acknowledgment of the distance between ourselves and our appointed happiness.

At certain moments, it is reason enough to live.

Yes, we despair because grief is a precondition of being alive, but I’m not sure Almond meant to imply that it was despair itself that gives one hope. Hope, I think, lives in the possibility of a shared realisation. It is our understanding of the universality and inevitability of this despair that connects us to each other and helps us endure and make meaning from it.

The words ‘So it goes’ have always belonged to the lexicon of pilgrims who understand that life sits still for no one, no matter how we came into the world or how we leave it. Nothing stops. Not time, not life, not death – or grief. In the end, might we all be pilgrims peregrinating through arcs of time, longing to close the distance between ourselves – our grief – and our ‘appointed happiness’? Might we see our aliveness amplified through this longing?

I think the ultimate ‘So it goes’ Vonnegut imagined for us is this: that we should know how lucky we are to have the mouth and breadth to say these words. That we might say them to each other with a softness that connects us, and the hope that perhaps one day somebody will say them over our own bodies, making a full-circle prayer that illuminates the miracle we were ever here to love and be loved at all.