We speak today of balanced performances, balanced tastes, balanced mental states, balances of power – the balance of nature itself. In all these cases, balance holds a valence so positive that it approaches an unquestioned ideal. The sense we have of its presence or absence in large measure determines our judgment of what is right or wrong, ordered or disordered, beneficial or destructive, safe or dangerous. Its opposite, imbalance, almost invariably signals sickness and malfunction. When we stop to think about it, we can recognise the enormous breadth of meaning we attach to our sense of balance, but we might also recognise, with some surprise, just how little we actually do think about it.

The same was true for the Middle Ages. Despite the central place that the ideal of balance occupied in virtually every area of medieval thought, it was almost never questioned or problematised as a topic in itself. And this raises a question: why did it, and why is it still, almost invisible as a subject of historical analysis?

I can suggest two reasons. The first is that our recognition of balance’s great importance to our psychological, intellectual and social life tends to encourage a biological and hence essentialist understanding of it. Balance is balance: we all know what we mean by it, we all trust our sense of it, we never imagine that this sense is changing, or even that it can change. For this reason, it is difficult for us to think of it in historical terms, as determined within specific cultural contexts, or as changing over time.

The second, equally relevant, is that balance lies beneath the level of conscious awareness. It is tied to a generalised sense, a wordless awareness, a diffuse feeling for how things properly work together or fit together in the world, extending all the way down to our discomfort when we see a picture hanging unevenly on a wall.

For this reason, I have argued that, rather than serving as the subject of thought, balance has traditionally served as the un-worded but pervasive ground of thought, exercising its great influence beneath the surface of conscious recognition. For the historian who has become aware of balance as an historical subject in itself, the first problem, then, is how to recognise the changes that have occurred to and within this un-worded sense over historical time. The second is how to uncover and reveal the profound intellectual effects these changes have made possible.

Between approximately 1250 and 1375, a manifestly new sense of what balance is, and can be, emerged. When projected onto the workings of the world, this new sense transformed the ways the workings of both nature and society could be seen, comprehended and explained. The result was a momentous break with the intellectual past, opening up striking new vistas of imaginative and speculative possibility.

The group of medieval scholars whose speculations most clearly reflected this new modelling of balance occupied the very pinnacle of their intellectual culture – brilliant innovators whose ideas stand out today for their boldness and their forward-looking elements. Indeed, the innovations these scholars pioneered, and the new sense and model of balance that made this innovation possible, provided both a first view of, and a fundamental foundation for, the emergence of modern science.

I speak of ‘models of balance’ because even though the complex sense of balance remained un-worded in the pre-modern period, it was far from unstructured. These models were (and still are) composed of a cluster of interlocking assumptions, perceptions and intuitions, characterised by a high degree of interior reflectivity and internal cohesion. Within any given intellectual culture, and at any given period in history, they possess a degree of internal order and organisation sufficient to allow them to be experienced as unified wholes, which adds greatly to their potential to influence the thinking mind. Though a product of history, they are felt to be ‘natural’, which further facilitates their absorption and acceptance.

Medieval Latin contained no word that maps seamlessly onto our modern notions of balance. ‘Equality’ (Latin, aequalitas) was the word that came closest, with the caveat that there were major differences between the meanings attached to their ‘equality’ and ours. Especially relevant in scholastic circles from the 13th century on was the capacity for aequalitas to express the idea of a complex proportional balance dynamically maintained between multiple elements of different weights and values, rather than the clear, exact and knowable one-to-one equation of previous generations. Moreover, they came to imagine the possibility that proportional equality could be maintained even within multi-parted systems in continuous change and motion. For example, they applied the word aequalitas to the complex proportional balance maintained within the working parts of the human body; to the political ideal of civic balance, sought and re-sought between multiple competing groups and interests within the civitas; to the ever-shifting proportional balance achieved between buyers and sellers bargaining freely in the marketplace; and all the way to the proportional balance that governs the moving order of Earthly nature and the cosmos itself.

Along with these expanded definitions of aequalitas, shared by an elite group of university scholars, the new modelling of balance came to encompass the intuition and idea that the created world was composed of a series of complex working systems, each capable of ordering and equalising itself internally, entirely through the dynamic interactions of their ever-shifting parts, and doing so (in a crucial departure for this period) in the absence of any overarching or all-directing master Intelligence. This particular model of balance, which emerged c1250-1350, represents the earliest clear anticipation of the modern scientific understanding of the word ‘equilibrium’, and hence I refer to it as ‘the new model of equilibrium’.

Relativity replaced hierarchy as the key to comprehending order and identity in both nature and human society

These are the six most characteristic, impactful and historically important components of the new model of equilibrium:

- Where formerly balance had been viewed as a precondition of existence, whether instilled into Creation by an all-knowing and all-powerful God, or inherent to nature and ‘natural order’ as asserted in the writings of Aristotle, now the focus shifted to the visualisation and exploration of complex functioning systems in which balance/aequalitas was imagined as an aggregate product, resulting less from any pre-existent plan than from the interior interaction of their multiple moving parts.

- Within the newly conceived self-balancing system, values and natures formerly fixed in their place by God or by nature were now assumed to be fluid and changeable, ever-shifting in relation to their changing position and function within the systematic whole.

- As this occurred, in what represented a huge intellectual break with the medieval past, relativity replaced hierarchy as the key to comprehending order and identity in both nature and human society. The working system was reconceived as a fluid relational field, with no hierarchical top or bottom, beginning or end.

- In the new way of imagining the working system, expanding and contracting lines replaced points as the basis of structure and activity, and concern with the details of continuous motion and change (now amenable to geometric representation) replaced the traditional search for essences and perfections.

- Given the recognition of the system’s ever-moving and shifting parts, the goal of full knowledge was abandoned in favour of relying on estimations and approximations, which were now recognised as the only ways that entities undergoing continual change can be measured and known.

- The inescapable indeterminism of the new relational model opened the door to accepting the philosophical legitimacy of reasoning in terms of probabilities and applying these to comprehend the workings of nature and society.

It is clear from this list just how complex and many-faceted the new model of balance was and how utterly intertwined were its elements. When a constellation of intellectual elements link to form a meaning-web of such complexity and reflectivity, its weight and potential impact on thought is multiplied far beyond the sum of its parts. The model becomes more than a collection – it becomes, in medieval terms, a ‘unity’ (Latin, unitas), which is to say, a coherent and cohesive whole. As such, it possesses a characteristic feel and even a characteristic rhythm, which can be literally sensed, even if it remains beneath the level of consciousness. It is, in short, the sensual presence possessed by models of balance that allows them their great weight and sway in the minds of the most sensitive and perceptive thinkers in every culture. Over the period 1250 to 1375, those intellectuals who came to sense and then apply the new model of equilibrium to their speculations, could see things, imagine things, and speculate on things that those who had not simply could not.

In searching for the factors underlying the emergence of the new model of equilibrium, there are four of primary importance: the influence of particular educational settings (in this case, the highly evolved setting of the medieval university); the influence of authoritative texts (often from the Greek and Roman past); the influence of major technological developments; and the lived experience of particular socioeconomic environments, especially those undergoing rapid and often destabilising change. Here I can only treat what I consider to be the most important of these in the period under consideration – the factor sine qua non – and that is the rapidly changing reality and perception of economic life in the cities of 13th- and 14th-century Europe.

The intellectual attempt to make sense of the complex processes of equalisation taking place in the urban marketplace in this period, following a century of unprecedented economic expansion on many fronts, almost required the imagination of new forms of balance and equilibrium. In retrospect, it is not surprising that the first university writings in which the new model of equilibrium appears nearly fully formed are late-13th-century scholastic attempts to comprehend the logic of commercial exchange in the urban marketplace. But rather than seeing the intellectual impact of this socioeconomic factor as unique to this time period, I would argue that in every culture and every historical period – including today – dominant forms of economic exchange shape the cultural modelling of balance on the deepest level.

The slightest knowable inequality in exchange was associated with the mortal sin of usury

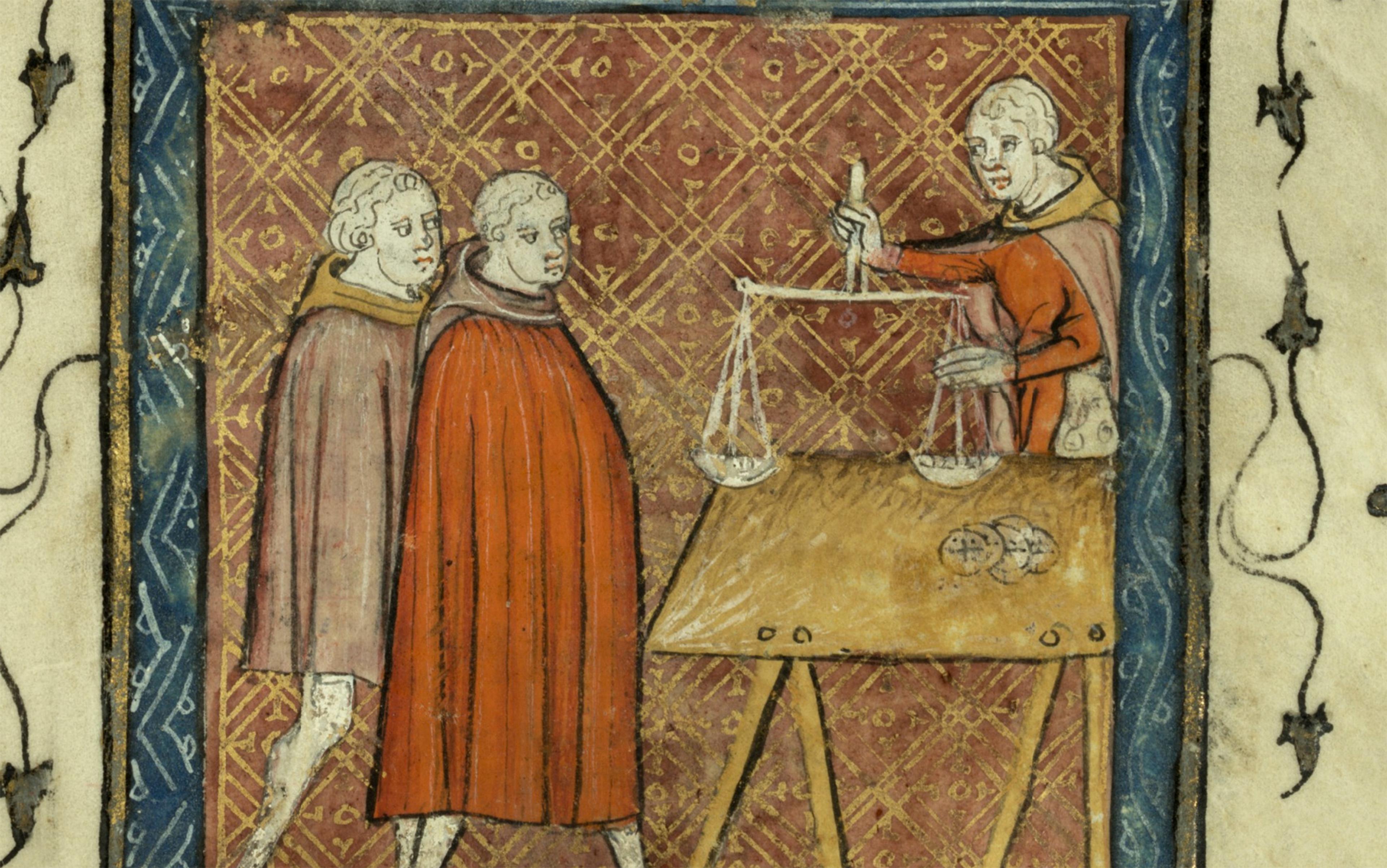

In virtually every philosophical, theological and legal text on the subject of economic activity written in the Middle Ages (and for centuries following), the required goal of all forms of exchange was defined as the establishment of an equality between exchangers. Writers termed this required goal ‘aequalitas’, and the identification of this word with the sense of achieving proper balance is fully apparent in the metaphors they applied. Scholastic writers universally identified the process of economic exchange as a complex process of balancing toward the goal of equalisation, even as, by the mid-13th century, they were coming to recognise that, in many cases, this economic ‘equality’ could be understood only as proportionally rather than numerically equal, as approximate rather than precisely knowable, and as shifting with respect to ever-changing circumstances in the marketplace, rather than fixed.

At the same time, however, and following the same logic that insisted on the maintenance of balance/aequalitas in all forms of exchange, the production of the slightest knowable inequality in exchange was associated with the mortal sin of usury, which was continually and vehemently condemned over the whole of the Middle Ages. At the root of traditional usury theory lay the demand for the maintenance of a perfect one-to-one equality between exchangers: for the lender to demand back from the borrower even one penny more in return was defined as manifest usury. This remained the case even as, beginning in the 12th century, huge advances in the economic areas of monetisation, commercialisation, urbanisation and market development transformed the economic landscape of Europe – a transformation so profound that modern historians now routinely use the term ‘Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages’ to refer to it.

With the implacable opposition to the inequality of usury as background over this entire period, leading scholars at the great universities of Paris and Oxford in the 13th century (including highly renowned Church lawyers and Christian theologians) nevertheless continued to expand their recognition that, in the broad areas of commerce, economic value is, for the most part, shifting and relational, rather than fixed and ordered to any hierarchy recognisable within God’s plan. They saw that the inescapable uncertainties surrounding most everyday exchanges vitiated any possibility that an exact and knowable one-to-one equality (or perfect balance) could be required between participants, much less enforced, as usury theory demanded.

Despite this, those who were coming to grips with the actual relativity and variability of economic value expressed confidence that a newly proportionalised, relativised and ever-shifting aequalitas could represent a legitimate form of exchange, side by side with the older and much stricter one-to-one form. No one at the time (or for centuries after) recognised the full implications of this development. As a totally unintended consequence, the ever-multiplying speed, volume and complexity of commercial and market exchange over the 12th and 13th centuries had the historic effect of pressuring, stretching and ultimately reshaping the notion of aequalitas itself and, with it, the un-worded sense of what balance is and can look like.

Many passages from economic writings in this period can be seen to illustrate this point. Consider the case of Godfrey of Fontaines. Faced with the continually debated question of what might properly constitute aequalitas in exchange (with the charge of usury always in the background), Godfrey was one of a number of philosopher-theologians teaching at the University of Paris who were coming to an intriguing conclusion. True, he admits, in most contracts of buying and selling, neither party can ever know, for certain, the value of the goods they are exchanging. Nor can they know, at the time of exchange, which party might benefit more from the exchange in the long term. Doubt, he recognises, is inescapable. Yet Godfrey was suddenly able to imagine, and to argue, that the very condition of shared uncertainty in itself produces an aequalitas sufficient to render exchanges licit and non-usurious. The unshakeable requirement for aequalitas in exchange has been met, he argues, as long as there exists an equal measure of doubt on the part of both buyer and seller.

When the requirement for equality in exchange can be satisfied by the equality of doubt it contains, and when a satisfactory exchange equality is established merely by the willingness of all parties to assume a similar doubt at a similar price, we have achieved a new, protean and potent understanding of both aequalitas and the potentialities of balance itself – one that had been vastly expanded over that of previous centuries.

Further expansion soon followed, as evidenced by a remarkable treatise on usury and contracts of sale authored in the 1290s by the eminent Franciscan philosopher-theologian Peter of John Olivi. Olivi’s treatise On Buying and Selling, On Usury, and On Restitution contains literally dozens of prescient economic insights. But even more remarkable than his individual insights was his unification of them within an overarching rationale – one that was sufficiently capacious, both to comprehend, and to theologically justify, some of the most dynamic economic realities of his day.

To give but one example: medieval writers employed many rationalisations to condemn usury and to insist that any violation of one-to-one equality in the loan is tantamount to a violation of both the divine and the natural order. Of these rationalisations, the most common held that money is inert and sterile by its nature and, therefore, for money to grow by itself or to multiply itself still represents a clear violation of the natural order, instituted by God. This understanding, supported by the philosophical authority of Aristotle, was fully supported by the early Church Fathers and enshrined in Church law. In reading Olivi, however, it soon becomes clear that he has arrived at a striking new understanding of the dynamic of monetised exchange in his society, and that at the core of this new understanding lay a reconceptualisation of aequalitas itself.

This is a clear vision of market exchange as a self-balancing system in dynamic equilibrium

To illustrate this here, I can present only one of his exceptional economic insights: his definition of ‘capital’ or what he calls capitale. In utter contrast to traditional claims for the sterility of all money, Olivi asserts that money, when in the form of commercial capital, is naturally fruitful, expansive and capable of multiplying, in its essence. When he first enunciates this principle, he writes:

money, which in the firm intent of its [merchant] owner is directed toward the production of probable profit, possesses … a kind of seminal cause of profit within itself that we commonly call capitale. And therefore it possesses not only its simple numerical value as money-measure, but in addition, a superadded value.

Merchants, he writes, not only presuppose that this superadded value ‘truly’ exists within capitale as the ‘seed’ of its fruitfulness, but he recognises that they are also skilled in rationally estimating the changing degree of this fruitfulness, as expressed in the continual rise and fall of its borrowing price, as commercial outlooks change from day to day.

Furthermore, since Olivi has come to recognise that it is the very nature of capital to multiply, he judges that merchants who buy and sell money for a fluctuating agreed-upon price do so without committing a sin against either nature or God, and thus, without committing the sin of usury. In Olivi’s judgment, rather than being condemned, these merchants should now be seen to satisfy the traditional requirement for balance/aequalitas in exchange – but only, of course, as he has now come to imagine, define and apply it.

Olivi’s revaluation of merchant capitale represents only one out of many in his Tractatus, in which he stretches the bounds of economic aequalitas beyond anything imagined before the mid-13th century. Taken together, the principles he enunciates to rationalise this new sense articulate virtually all the major elements constituting the new model of equilibrium.

At its base is a clear vision of market exchange as a self-balancing system in dynamic equilibrium, in which the free interchange of individual exchangers, each desiring the unequal goal of buying cheap and selling dear, produces – somehow – not only a balance/aequalitas between individual exchangers but, far beyond this, a balance/equilibrium that extends to the systematic whole of the urban marketplace. The end result was a remodelling of aequalitas itself, and hence of balance itself, in the direction of a new vision of the potentialities of systematic equilibrium: shifting, relational, multi-proportional and knowable at best through approximation and probability – a direction that had been literally unimaginable in European culture for centuries past.

Consider now the ways of seeing and comprehending the world that the intuition of the new model of equilibrium made possible. I can follow here only a single fertile example taken from the realm of natural philosophy in the area we today recognise as geology.

Jean Buridan was an honoured teacher in the School of the Arts at the University of Paris from the late 1320s through the 1350s, and among the greatest philosophers of his time. Many of his writings reveal what had become newly possible to think, to envision and to imagine by the first half of the 14th century, as a result of the new modelling of balance in the direction of equilibrium. At the beginning of his Commentary to Book 2 of Aristotle’s treatise On the Heavens, and in response to a seemingly minor observation of Aristotle’s, Buridan raises a question with large implications: ‘Whether the whole of the Earth is habitable?’

He recognises that three-quarters of the Earth’s surface lies below the sea, while only one-quarter lies above and is habitable for humans. To the extent that there was a traditional Christian position on his question, it held that the portion of habitable Earth had remained roughly the same since creation, planned that way by a benevolent God, or by benevolent nature, to serve the benefit of humankind. But Buridan is not satisfied with this. Although he is both a devout Christian and a deeply committed Aristotelian (as are nearly all the leading university scholars in his day), he looks for his answer here not in God’s fiat nor in what Aristotle had to say (or not say) on the subject. Rather, throughout this question, he relies heavily on his own observations and powers of reasoning, and his own sense of physical possibility, in which his sense of balance plays a major part. He then reasons that, given the spherical nature of the Earth, and given that all earth falls naturally toward the Earth’s centre (as Aristotle maintained), and given the great over-abundance of water with respect to land and, finally, assuming along with Aristotle that the Universe is eternal, he is led to ask why, in the fullness of time, should any portion of land remain dry above the waters and habitable?

One possibility Buridan raises is that the Earth’s highly uneven surface renders its mountainous heights insurmountable by water. But he quickly dismisses this on the basis of what he has observed with his own eyes: the process that we today call erosion. All streams, he writes, continually carry bits of earth ever downward to the sea – and this takes place perpetually, even at the summits of the highest mountains. ‘Thus,’ he concludes, ‘through an infinite time these mountains ought to be wholly consumed and reduced to a sphere [beneath the waters].’

He views the totality of geological displacement over eternity as a grand self-balancing system

There are a number of startling assumptions here. Buridan’s eternal world is about as far as you can get from the biblical time-world of 6,000 years or so that medieval people are generally supposed to have accepted without question. But thinking in Aristotelian eternal time rather than Christian time, Buridan projects that, if erosion continues over eternity, then even the highest mountain will eventually be washed into the sea. But more striking still, he reasons that if the world really is eternal, as Aristotle asserts, then all the earth that was once above the waters has already been washed into the sea.

Having concluded this, based on observation, logic and his sense of physical possibility, Buridan is faced first with the problem of explaining the continued existence of any dry land whatsoever into the present. And then he takes on a yet-harder intellectual task: given that he sees erosion as an eternal process, and given that therefore every portion of dry land will eventually be taken into the sea, he tries to imagine a physical system that can explain not only why some dry land will be continually preserved, but why the same exact proportion of dry land will remain eternally constant at one quarter above the sea to three-quarters below, as he has assumed it is at present. But how would this be possible?

To answer this question, indeed, even to ask this question, Buridan imagines the whole of Earthly nature as an integrated physical system in dynamic equilibrium (to put it in modern terms). He then invents an elaborate physical explanation, which, as he writes, ‘seems probable to me and by means of which all appearances could be perpetually saved.’ He views the totality of geological displacement over eternity as a grand self-balancing system, functioning entirely on physical principles. Heat and cold cause evaporation and condensation, which in turn differentially rarefy and condense earth and water, which results in a continual interchange between relatively light particles of earth coming to the surface of the water, while relatively heavy particles descend to the depths.

As a consequence, he speculates that while parts of earth are being continually washed into the sea at multiple parts of the globe, an identical quantity of earth is being raised above the circle of the waters at other parts, eventually accumulating there to produce the very same mountainous heights that are being worn down elsewhere. Indeed, he explains the current existence of high mountains on Earth as the natural product of the perpetual cycle of erosion and accumulation in eternal equilibrium.

We can easily superimpose the one-to-one form of the mechanical balance on Buridan’s model here: as one mountain slowly disintegrates and disappears under water due to erosion, another slowly accumulates and rises somewhere else on the globe, in perfectly balanced measure. Buridan, however, envisions not one active balance, but a near-infinity of them, covering the whole of the shifting Earth over all eternity. His model of activity is purely relational, driven by its own internal logic, and governed by his new sense of physical necessity.

It begins with recognisable elements from Aristotelian physics, but there is something deeper within it that pulls and pushes the pieces into a new formal arrangement, allowing him to reimagine the quantity of earth above the waters at any moment as an aggregate product of systematic activity in perpetual equilibrium, rather than the result of a purposeful order, minutely managed by an overarching Intelligence. The deeper element underlying Buridan’s profound re-imagining and re-thinking here is not a concrete, expressible idea of balance (which he never mentions) but rather, as I have argued, a charged new sense of the potentialities of balance, active beneath the level of conscious recognition. And yet it is capable of literally moving the Earth and, in the process, radically redefining how the natural world works and succeeds in maintaining itself in order.

Here we can see the great Aristotelian commentator thinking in ways that had previously been unthinkable. Also previously unthinkable was Olivi’s re-visioning of commercial capital as naturally and essentially fertile, fruitful and expansive, when previously in this culture the idea of money as fertile had been forcefully condemned as monstrously ‘unnatural’. But how does the definition of what is ‘natural’ shift radically within an intellectual culture? How does the unthinkable become thinkable – the unimaginable imaginable? What is it that causes vital new questions to rise to the surface and potent new answers to be envisaged and argued? Each of these transformations (and more) appear in field after field of knowledge between 1250 and 1350, pioneered by those thinkers who shared in the intuition of the new model of equilibrium.

This has led me to conclude that a focus on the history of balance, and a close analysis of the varying constellation of elements that constitute emerging models of balance, can become a potent new tool of historical study, particularly when addressed to major ideas that have proven to be exceptionally innovative and fruitful. And my strong supposition is that this is true not only for medieval intellectual culture, but for other cultures and other time periods as well, right into our present.