Few ideas are as unsupported, ridiculous and even downright harmful as that of the ‘human soul’. And yet, few ideas are as widespread and as deeply held. What gives? Why has such a bad idea had such a tenacious hold on so many people? Although there is a large literature on the costs and benefits – psychological and economic – of traditional religion, there is a dearth of comparable research on religion’s near-universal handmaiden, the soul. As with Justice Potter Stewart’s non-definition of pornography – ‘I may not be able to define it, but I know it when I see it’ – the soul is slippery and, even though it cannot be seen (or smelled, touched, heard or tasted), soul-certain people seem to agree that they know it when they imagine it. And they imagine it in everyone.

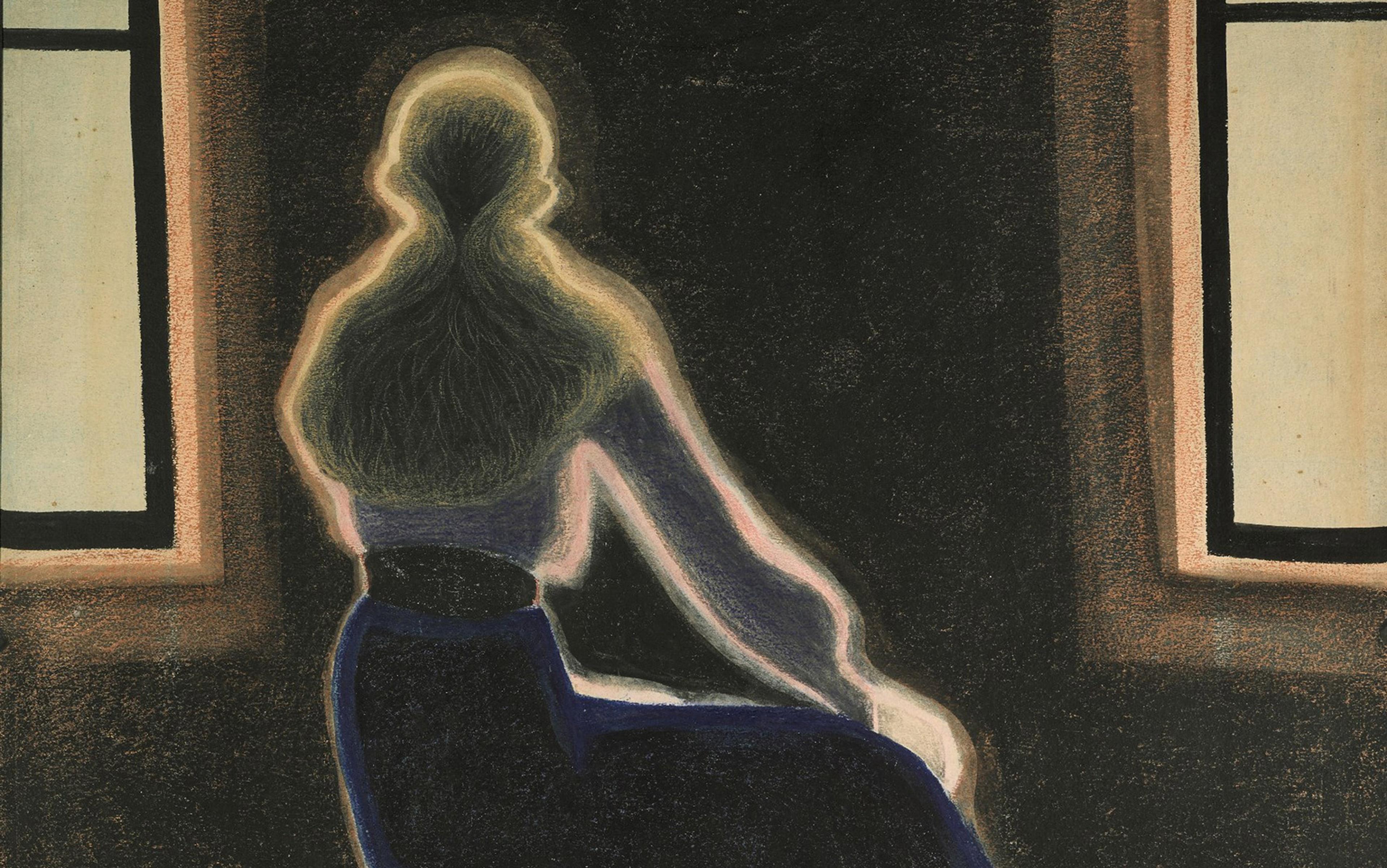

Viewed historically and cross-culturally, there is immense variation regarding the soul, although some patterns can be discerned and are nearly universal. Souls are said to reside inside their associated bodies and are pretty much defined as immaterial, thereby contrasted with their fleshy habitations. Immortality is another close, but not quite universal, characteristic. Also widespread, but not invariant, is the soul’s ability to travel independent of its body, sometimes after death but often during sleep. Dreams are widely seen as demonstrating not only that the soul is ‘real’, but that it occupies its own unique plane of reality.

Jewish doctrine says almost nothing about the soul. ‘[T]here is no way on earth,’ wrote the influential Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, ‘that we can comprehend or know it.’ This agnostic attitude is consistent with Judaism’s lack of specificity regarding the afterlife generally and of heaven and hell in particular. By contrast, Christianity and Islam are clear when it comes to the soul, conceiving it as immaterial as well as immortal, the two perspectives being, as it were, soulmates. Although Islam has a variety of views when it comes to the soul, there is greater diversity within Christianity – between Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox conceptions – and also within Protestantism, ranging from evangelical fundamentalism to the more relaxed and philosophical approaches of modern-day Quakers and Unitarians.

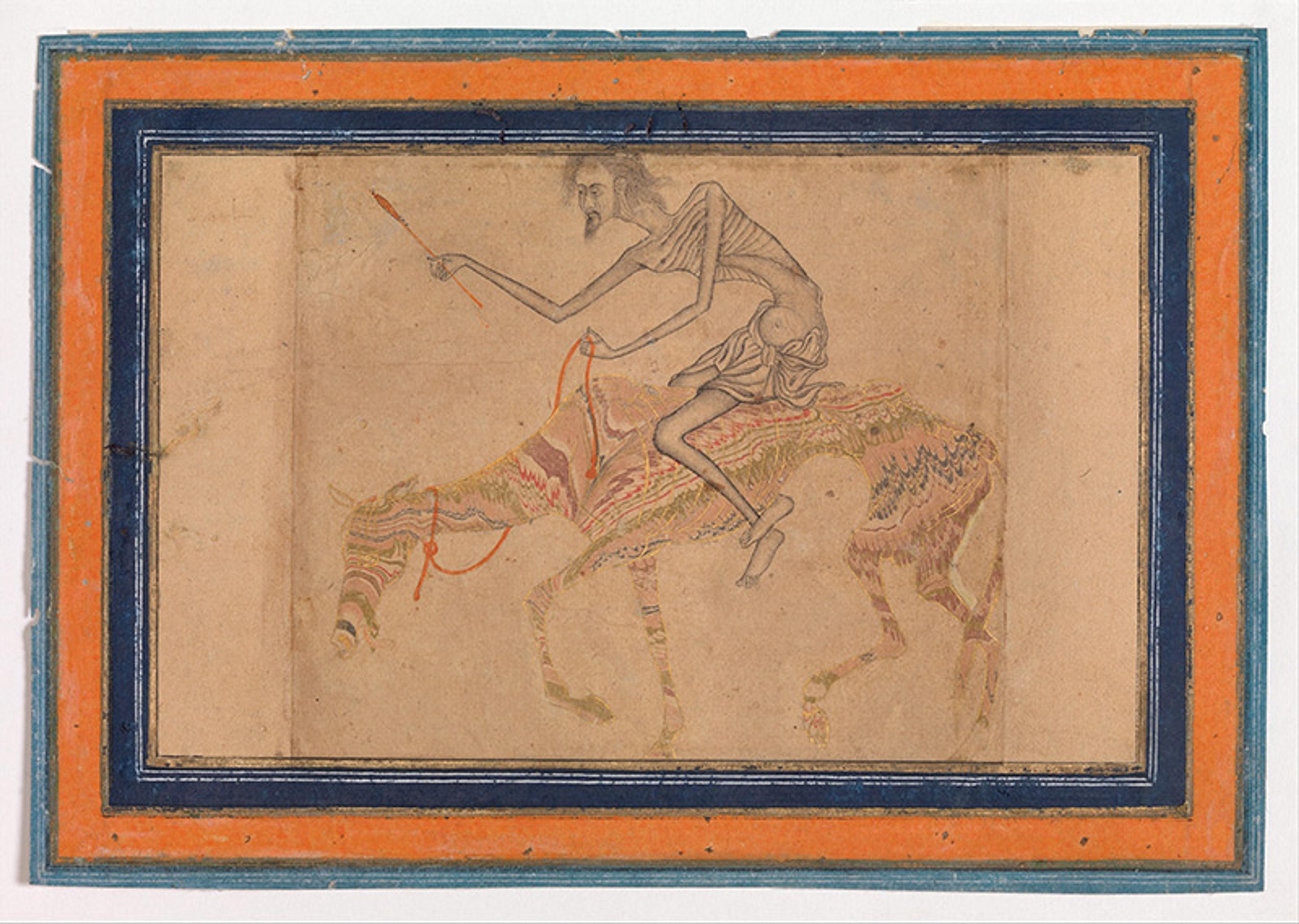

The Hindu soul resembles its Abrahamic counterpart with regard to immateriality and immortality, but with two major differences. For one, the soul (atman, or ‘self’) is conceived as a personalised part of a greater world-soul (brahman, closer to the Western ‘God’). Second, the Hindu soul is subject to regular reincarnations following the death of its body, including excursions into different kinds of animals, depending on its accumulated karma. The final desired destination of this process of repetitive birth and rebirth – oversimplified as nirvana – somewhat resembles the Western concept of heaven, although it is conceived more as a respite from the cycle of birth and rebirth than as an abode of ongoing bliss.

When trekking in the Himalayas, I often followed the sherpa advice that one should pause every third day, ‘to let your soul catch up with your body.’ It made a kind of intuitive sense. One needn’t be a Buddhist or travelling at extreme elevation to appreciate this wisdom. As a metaphor for mind, consciousness, one’s deeper beliefs and desires, the soul is serviceable. But its appeal goes beyond linguistic or conceptual utility.

Whatever else the soul is supposed to be, it is immaterial: ie, lacking physical substance. That doesn’t necessarily mean it doesn’t exist, because other ‘things’ without structural reality are real as immaterial concepts: love, fear, hope, and so forth. Some things exist only as genuine objects, rather than in the realm of the ideal or the conceptual: chairs, fire hydrants, trombones. There is no reason to discount the soul simply because there is no universally accepted sense of what it is. Just as one person’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter, one person’s conception of the soul as possessing a spark of the divinely supernatural may be another’s mind, free will, conscience, and so forth.

But no one claims that personal memories or the Pythagorean theorem are imbued with a God-given spark, or that they exist in the sense that they can be bartered and commodified like the soul, which can by some accounts be sold to the devil (suggesting that it is at least somewhat concrete). Nor are immaterial concepts supposed to reside within each person, to disappear – and then re-emerge elsewhere – after the death of the body. Soul-zealots do not accept that it exists only in a hazy, ectoplasmic plane: our unique dose of fairy dust. It is purportedly real, albeit not quite like the body in which it resides.

Immateriality – especially when blindly accepted but not seriously interrogated – is useful to the soul’s mythology, because failure to see, hear, smell, touch or taste that which is immaterial isn’t a dispositive argument against it. For believers, the fact that the soul cannot be perceived by the senses becomes an argument for its superiority, because it doesn’t partake of the messiness and dross of our everyday, fallen world. That is one of the soul’s great attractions.

Modern science hasn’t yet come up with an alternative answer to what, precisely, makes something alive

It is also deeply flattering to be told that part of oneself is a chip off the old divine block, all the more so given that the devil is desperate to get it from you, while religion – acting as God’s representative – is equally eager to save it for you. How empowering to be told that we possess something uniquely our own and, moreover, that it is of inestimable value, no matter one’s station in life. Like the Colt-45 in the Wild West, souls are great equalisers. At the same time, souls are paradoxically delicate and must be guarded like a Victorian maiden’s virginity, lest it be lost and you ruined – not merely excluded from a secular marriage market, but consigned to ruination that is potentially eternal, deprived of union with God and, in the worst case, consigned to eternal torment.

The soul’s alleged immateriality offers yet more psychological appeal. For one thing, the difference between alive and dead is profound. The eyes are bright and busy, then dull and unresponsive. Movement occurs, then ceases. No wonder life itself has long been associated with a kind of magic substance: now you’ve got it, now you don’t. And, when you don’t, it’s because your life-force, your soul, has departed. Or maybe it departs because you’ve died, and your soul is obliged to move on. In many conceptions, the soul is that which breathes life into a body, and even modern science hasn’t yet come up with an alternative answer to what, precisely, makes something alive. (Worth mentioning at this point: soul-believers are inclined to point to what-science-doesn’t-know as evidence for the supernatural. This is the ‘God of the gaps’ argument, namely that God is posited to explain gaps in our scientific knowledge, a viewpoint that is discomfiting to theologians because it brings two big problems. For one, attributing what we don’t understand to God hardly suffices as an explanation. And, for another, as science expands, the gaps shrink – and in the process, so does God.)

Life-death transition isn’t the only popular testimony for the existence of some sort of immaterial, internal component of the self. Cartesian dualism, whereby mind is believed to be somehow distinct from body, is uniformly rejected by scientists and even by much of the lay public insofar as they acknowledge that mental activity derives strictly from the brain. And yet we experience ourselves as something different from our material body, speaking of ‘our thoughts’, ‘our desires’, ‘our memories’ and the like, as though each of us resides inside ourselves, along with a concatenation of thoughts, desires, memories, rather than the disconcerting truth that there is no ‘self’ separate from the material functioning of our neurons.

Add to this the universal experience of feeling disconnected from our bodies, not as a result of psychosis, but just in daily life. The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak: ‘we’ might have plans, but our body disagrees. On occasion, an erection (or its absence) is inconvenient; ditto for a nursing woman’s letdown reflex, or any number of cases in which it appears that one’s body doesn’t cooperate with what we perceive as our hopes, inclinations and desires. Given all this, it’s hard not to be a dualist, hence hard not to feel that there’s something about ourselves that is distinct from our bodies, the Cheshire Cat’s grin after the cat’s body has disappeared.

Moreover, we know our bodies to have been mutable, while also feeling that our inner self has remained independent of any merely meaty transitions. Our memories yield a kind of mental continuity, a persistence of personal identity that feels separate from whatever happens to our bodies. This is why, even as we recognise the absurdity of Gregor Samsa being transformed into a giant insect, or Odysseus’ crew into pigs, we also readily accept that Samsa et al somehow remain themselves underneath, or inside. Even those of us who don’t accept that souls exist, that they commute, transmute or travel, can nonetheless find such ideas emotionally comprehensible. Somewhere (deep in our souls?) we are intuitive soul-sympathisers.

But we are also intuitive flat-Earthers. Our intuitions are often wrong, whether about the magical elixir that seems necessary to underlie life or the immaterial, dualistic intervention that jumps the gap between neurons and mind. This intuitive misconstrual contributes to why even the most sceptical observers unthinkingly resonate with the soul’s immateriality, and also helps explain why belief in the soul is so widespread.

There is more. The allure of the soul goes beyond its attractive immateriality. Take death. Admittedly, most of us would rather leave it, and that’s the point.

Immortality is a big deal. It is impossible, at least in the Abrahamic traditions, to imagine a soul that isn’t immortal. A consistent defining feature is that, whatever else it is (how it arises, when it arises, where it resides, what it does to facilitate the functions of our body, where it goes after that body’s death, whether or not it is corruptible), a major appeal of soul-belief – probably its greatest – is that it promises eternal life. Not for the body, of course, but for itself, and thus, somehow, for each of us. No one would yearn for immortality if it were not for death and the near-universal desperation to avoid it, or at least to transcend it by having some part of ourselves persist afterward. Somehow. Somewhere. Some time.

Even the most devout believers in a truly divine afterlife do what they can to keep from dying. (‘That’s the last thing I’ll do,’ quipped Groucho Marx.) And those who don’t, or who claim that they don’t, announce that they don’t have to, because death isn’t such a big deal. In his ‘Holy Sonnet 10’ (1609), John Donne proclaimed:

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou are not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

The poem ends: ‘And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.’ It may be churlish to point this out, but Donne did in fact die, while death didn’t. Although the evidence is now overwhelming that many different species of animals such as elephants and chimpanzees are aware of death when it befalls others, and some even appear to mourn when a relative or sometimes an unrelated group member dies, it does not seem that any animal except ourselves is afflicted with awareness that someday they, too, will die. Despite numerous Donne-like assertions about overcoming the fear of death – not to mention transcending death itself – the effort, energy and hope thereby expended speak eloquently of how real and threatening is that fear. Hence the paradox that even those who deny its importance go to great lengths to delay if not prevent it. Moreover, even the most religiously devout are most concerned to establish and reinforce confidence that eternal life is available, unspeakably delightful, and just around that final corner. Just waiting for their souls to get there.

Ghosts bad; souls good. Both are inseparable from the fear of death

In many non-Western traditions, funerary rituals are required for the deceased’s soul to make it to heaven. I have witnessed ‘sky burials’ in Tibet and northern Nepal, in which the corpse is laid out on a high, flat plateau, its body ritually sliced open and made available to vultures, while mourners chant encouragement to the deceased’s soul, which is thought to take flight along with the newly engorged birds, thence to proceed, after taking its obligatory tour in the upper air, to relocate itself in other bodies, either human or non-. When I asked one of the celebrants what would happen to the soul of the dear-departed if these procedures were not followed, the response was that it would remain trapped within the decaying body, where it wouldn’t be happy. And that, despite being eternally imprisoned, it would somehow exact revenge upon those who let it down. (Another English-speaking Tibetan said, with a wry smile, that she thought the only unhappiness would be some underfed vultures.)

Despite all the Christian gospel (derived from the Old English for ‘good news’) about post-mortem souls cavorting happily in heaven, there persists a widespread assumption, also cross-cultural, that after death the deceased’s spirit becomes frightening, as witnessed by the expectation that anyone whose sky burial is ignored or inadequately carried out will revenge themselves on the living. Ghosts are nearly always feared and unwelcome, except when they are made the butt of humour. Ghosts bad; souls good. Both are inseparable from the fear of death and the hope that mortality can somehow be avoided or at least shoehorned into eternal life, via our undying souls.

In ‘Aubade’ (1977), perhaps the finest poem of the many written on the subject, Philip Larkin noted that, when it comes to death, there is ‘nothing more terrible, nothing more true’. He goes on:

This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die …

Larkin sombrely concludes that: ‘Most things may never happen: this one will.’ Managing this situation is challenging. Thank God – and our credulity – for our immortal souls! Our body, like John Brown’s, will lie ‘a-moldering in the grave’, but our soul will ‘[go] marching on.’ Hallelujah!

Once again, there is more. Whereas the allures just described are largely neutral, or even beneficial to individual psyches, two others are especially congenial to institutions, and both are largely malign. One is the widespread presumption that souls are uniquely possessed by human beings, leaving all other living things bereft of divine connection and accordingly, denied moral legitimacy. To be sure, there are laws against abusing animals, but for the most part they are half-hearted and not zealously enforced. Scratch the surface, and much of the underlying substructure justifying maltreatment of animals derives from the unspoken but widespread instructions provided, for example, by the Hebrew Bible, in which Homo sapiens is given dominion over the Earth’s creatures, a dichotomous distinction that is keyed to the theological distinction of soulful vs soul-less.

The most fundamental take-home message from evolution is the continuity of living things. We share more than 98 per cent of our DNA with other apes, and around 90 per cent with cats. And yet one of the most consistent messages of monotheistic religion, and one that relies heavily on the concept of the soul, is discontinuity: there are human beings, and then there is everything else, never mind that we share basic patterns of anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, neurobiology, embryology and the like with the rest of the organic world. As Rudyard Kipling’s Mowgli understood: ‘We be of one blood, ye and I.’ We converge with the rest of life in every way imaginable, except, we are told, when it comes to souls. Never mind that basic biology demands that either souls are fictitious and no one has them, or we have souls and other animals do, too, perhaps to varying degrees: if each person has 100 per cent of a soul, then do chimps and bonobos luxuriate in perhaps 99 per cent, gorillas 98 per cent, and cats 90 per cent? No matter. When it comes to souls, we have ’em and they don’t, so we can round them up, keep them in inhumane conditions, skin them and eat them.

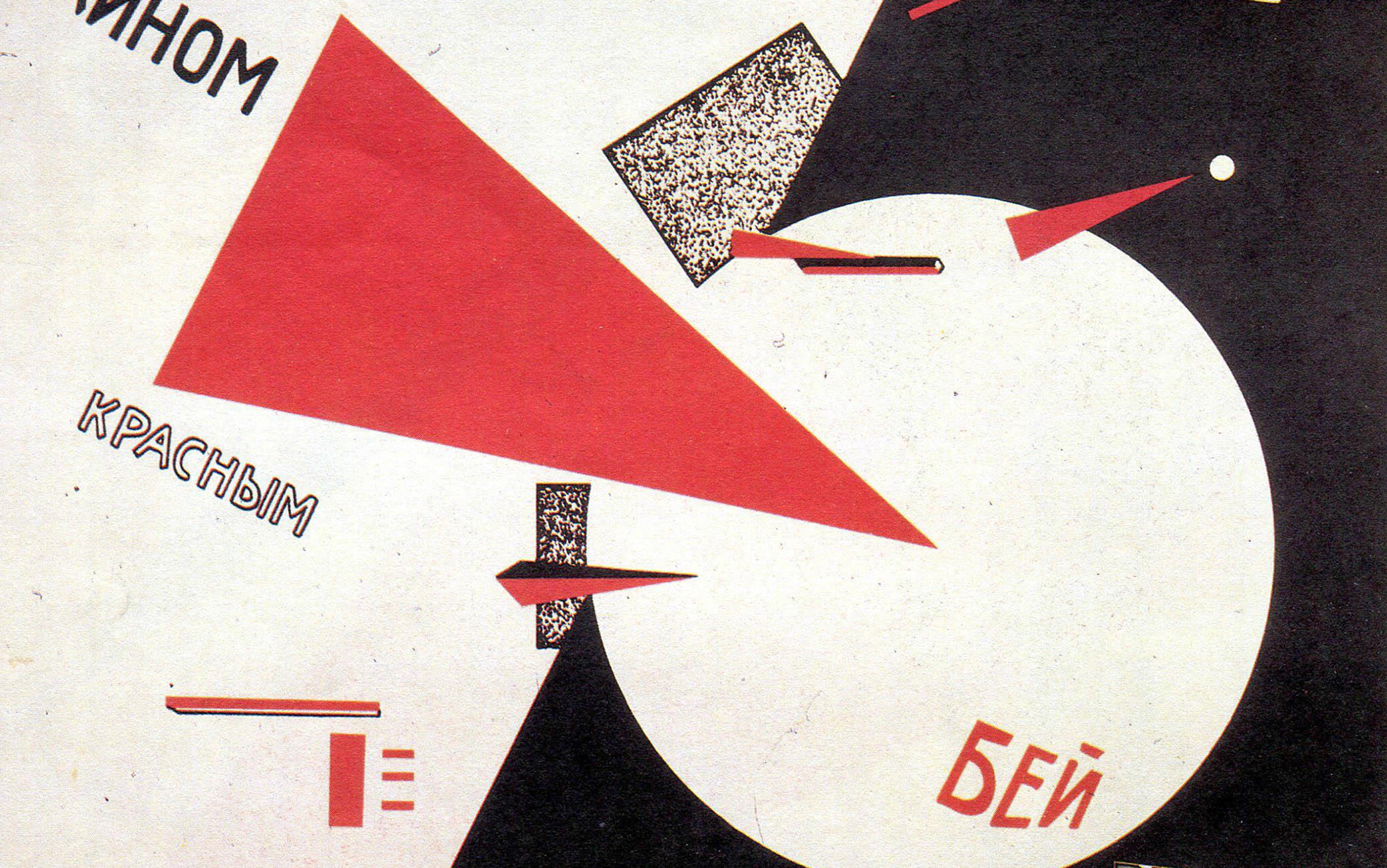

The second malign allure involves the threat of eternal punishment. The soul has been an especially useful arrow in the quiver of religious institutions, inducing terrified followers to do as they are told, or else: ‘Nice soul you’ve got there. A shame if it ends up in hell.’ A long tradition, especially in Christian and Islamic theology, anticipates that evil-doers will get it in the end, if not in this life, then in the next. The Hindu and to a lesser extent Buddhist concepts of karma apply here as well, although with somewhat less terrifying resonance: be good, and your soul will end up in a happy, admirable body, or perhaps even achieve nirvana. Be bad, and you (ie, your atman) will find itself stuck inside a cockroach or a snake.

There could be no suffering in hell without some sort of something that is available to be punished

In the Abrahamic world, it is entirely possible that holding hell over the heads of malefactors results in behaviour that is more prosocial than it would be otherwise, leading many to claim that without God and the threats that he imposes, morality would be defunct. (Cue Ivan Karamazov.) If so, then the soul serves many masters in addition to satisfying a need for immateriality, immortality and facilitating our abuse of other animals. The hard-working, multitasking soul provides a handle whereby the major religions induce people to do their bidding, not merely to avoid disappointing God but to keep eternal damnation at bay.

When hell is invoked literally, as it has been for most of the past 2,000 years, notably in the Christian and Islamic worlds, it is taken seriously indeed. It is worth emphasising that damnation after death presumes that souls are real because there could be no suffering in hell without some sort of, well, something that persists after death and is available to be punished. Those truly lost souls must carry with them responsibility for sins committed when their bodies were alive. So, let’s not lose sight of the conceptual realities hiding in plain sight: no sinning, no torments. No soul to have sinned, nothing to punish post-mortem. In short: the soul is a necessary, sufficient and convenient handle whereby religious authorities browbeat their followers, whether – according to doctrine – for the salvific benefit of those souls or for the functional benefit of those authorities.

Soul-based admonitions have traditionally focused on the prospect of misery after death rather than during life, mostly because it is all too apparent that bad people often do well in this life, while good people suffer, with no sign that justice ultimately triumphs. Hence, it can be helpful to think that sinners and other evil-doers will eventually ‘get theirs’, while the righteous will receive their just rewards. Perhaps claims of a punishing afterlife satisfy a widespread need to balance the scales of justice, to make the Universe fair when our mortal life isn’t.

As a way of manipulating the living, its power has long been recognised, by, among others, non-Christians such as Voltaire, whose sardonic Philosophical Dictionary (1764) includes the following reply to someone who had the effrontery to question the existence of hell: ‘I no more believe in the eternity of hell than yourself; but recollect that it may be no bad thing, perhaps, for your servant, your tailor, and your lawyer, to believe in it.’ The narrator goes on to observe the following:

[T]o those philosophers who in their writings deny a hell; I will say to them: – Gentlemen, we do not pass our days with Cicero, Atticus, Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus … In a word, gentlemen, all the world are not philosophers. We are obliged to hold intercourse and transact business, and mix up in life with knaves possessing little or no reflection, – with vast numbers of persons addicted to brutality, intoxication, and rapine. You may, if you please, preach to them that there is no hell, and that the soul of man is mortal. As for myself, I will be sure to thunder in their ears that if they rob me they will inevitably be damned.

More than two centuries before the Protestant Reformation, a popular focus on hell and its punishments had been especially intense, of which the most renowned and influential depiction was (and still is) Dante Alighieri’s magnificent poem The Divine Comedy (1308-21). It is interesting that Inferno, with its exuberantly graphic depiction of the tortures of hell, has always been read more widely and enthusiastically than Purgatorio or Paradiso, the other two parts of Dante’s masterpiece, although the latter are written with no less verve and brilliance.

Maybe this is testament to a deep-seated fascination with the grotesque, combined with a hefty dose of Schadenfreude along with genuine concern about what might be awaiting the sinful, even though – in its specificity – Inferno simply reveals the immense imagination of Dante and his yearning to get even with his Florentine enemies rather than any particular teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, then or now.

Robert Burton’s 17th-century treatise The Anatomy of Melancholy is a prescient account of what today is labelled depression. In it, Burton noted: ‘[I]f there be a hell upon earth, it is to be found in a melancholy man’s heart.’ For all the presumed psychological payoffs provided by soul-belief, it seems that one way to increase human melancholy is to bring hell upon Earth by threatening one’s soul with a forthcoming helluva hard time.

So, where does this leave those of us who maintain in our hearts and non-existent souls that the whole business is a load of nonsense and hurtful to boot? Let’s face it: soul-belief is liable to persist about as long as souls themselves are purported to endure. Soul-sceptics can make their arguments but should probably also recognise that this concept fits so neatly into the human psyche that it will not be readily dislodged. We’re not stuck with souls, but most people are likely stuck with believing in them.

Parts of this Essay are based on the book Threats: Intimidation and its Discontents (Oxford University Press, 2020) by David P Barash.