It was confusing. When the novel coronavirus hit the world in early 2020, Sweden of all countries chose to ignore the global consensus that favoured lockdowns and severe restrictions. Better known for its interventionist welfare policies, Sweden suddenly seemed to have become a European version of Texas by putting individual liberty before the collective good. The liberal New York Times dubbed it a ‘pariah state’ and accused Swedish politicians and health officials of keeping Sweden open for economic reasons. At the other end of the political spectrum, Right-wing American radicals who demonstrated against government restrictions carried signs calling for their leaders to follow Sweden’s example. Perplexing to all, the spectacle – or spectre – of a ‘libertarian welfare state’ loomed.

This story is not new but a reversal of an old one. Traditionally, the Left has held up Sweden as a beacon of social solidarity, while the Right has lamented the lack of individual freedom. Now Dr Jekyll had turned into Mr Hyde – or maybe the other way around, depending on one’s political inclinations.

But was it really such a dramatic turnabout? There was always something simplistic about the presentations of Sweden in the United States and elsewhere as a model for egalitarianism and social engineering. Though a readymade for progressive politics, it has seldom been based on any deeper understanding of Swedish history and culture. Sweden has, it turns out, never been the socialist paradise some outsiders have imagined – nor is it the libertarian haven it has been made out to be today.

In reality, Sweden is sui generis. To understand Sweden, it is necessary to begin with the tug-of-war between two powerful human impulses: the desire for individual sovereignty and the unavoidable necessity of being part of society. To describe this condition, the 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant coined a phrase that has since become a classic concept in social thought: der ungesellige Geselligkeit, ‘asocial sociability’. We humans, he claimed, have an innate impulse to associate with our own kind. We must be part of a community, not merely to survive but in order to develop our innate abilities. But this requirement, both ethical and necessary, also elicits from the individual a kind of resistance that threatens to dissolve the community.

All human beings, Kant argued, have a predisposition to isolate themselves, rooted in a desire to arrange everything according to their own fancy. And yet this contradiction is not merely some tragic circumstance that condemns humanity to unending unhappiness. In fact, as the 19th-century Swedish philosopher Erik Gustaf Geijer saw, movement between community and autonomy serves to strengthen each element:

The more individuals seek to detach themselves, the more acutely they feel the baleful nature of this necessity, which, even under conditions of reciprocal hatred, forces them to forge ever-closer bonds of mutual dependence.

Confronted by this existential paradox, all societies have sought to find a balance between the imperative of social virtues and the individual’s desire for freedom. However, the solutions to this universal dilemma have differed around the world. Some societies have erred on the side of social and political control, minimising individual freedom. Others have sought to diminish state interference in the private domain, and instead trust in the market, families and voluntary solidarity in civil society. Sweden is of interest because it has created a social contract embracing a strong state but in the service of an extreme form of individual autonomy. It has not compromised in either direction but has embraced the Kantian paradox head-on – and with gusto.

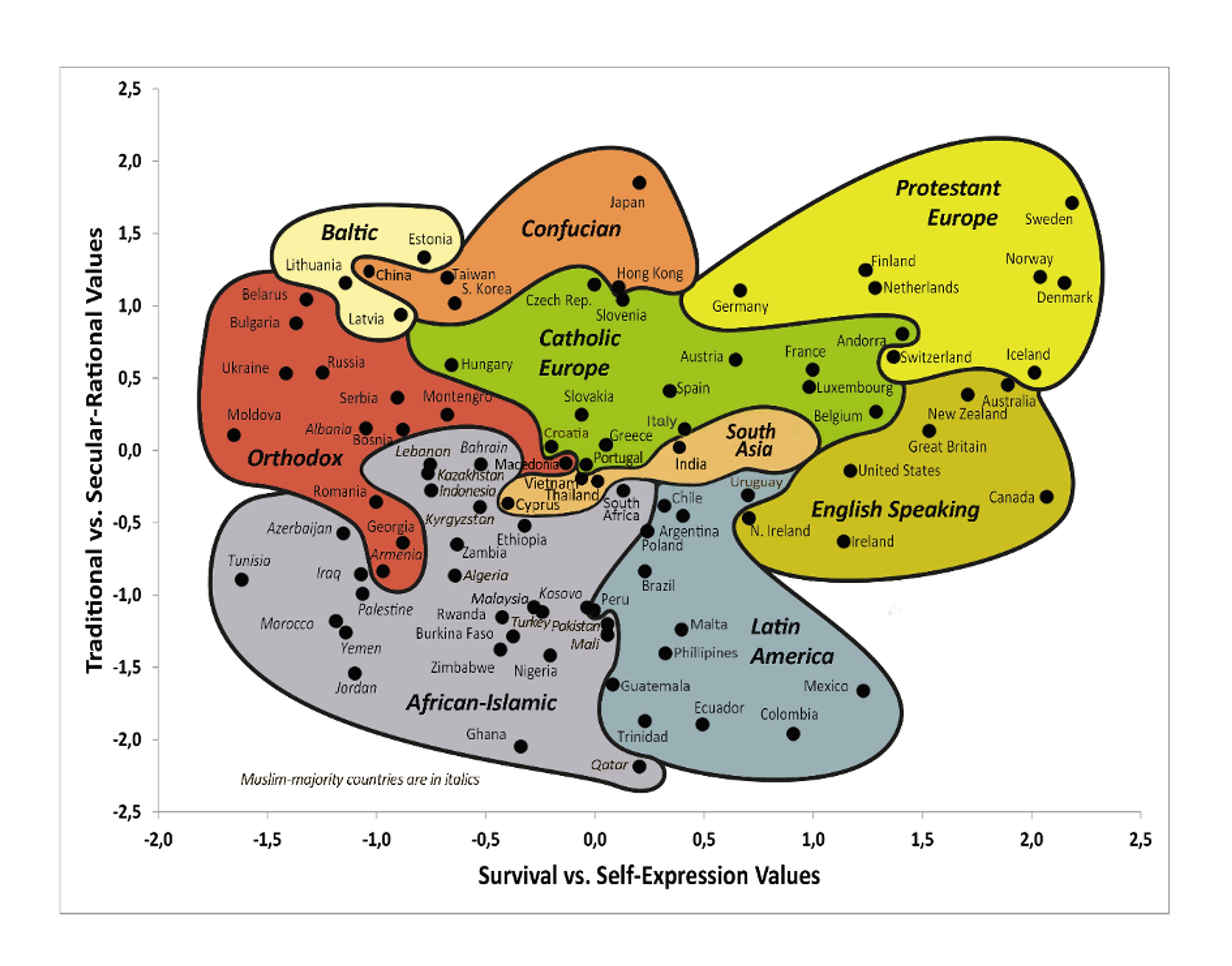

We may study this social contract from two directions. From above we can trace the institution-building, which shows that the hallmark of modern Sweden – which is not so much a model as a historical product – is that it claims to offer its citizens freedom from the traditional bonds of community without jeopardising the moral order of society. In a seeming paradox, Sweden has managed to combine high levels of social trust and a faith in collective institutions with an affirmation of individual autonomy. As comparative studies of social trust – as well as trust in institutions – show, Sweden stands out as a high-trust society along with other countries (Germany and Austria). At the same time, as the World Values Survey (2017-22) data show (see Figure 2 below), Sweden is also extreme when it comes to the stress on values that emphasise self-realisation as well as those that view the individual, rather than family, clan, religious community or ethnic group, as the fundamental units of society. This stress on individual autonomy is in turn linked to related values such as attention to gender equality, children’s rights, and the rights of sexual minorities. The name I have given to this alliance between state and individual is statist individualism.

But to fully understand this social contract we must also ask the crucial question of what has made this arrangement popular among the citizens of Sweden at the individual, existential level. After all, the institution-building that since the 1930s has transformed the country coincided with the democratisation of Sweden, itself a gradual process that unfolded over the course of the 20th century. At first, it included just men – and only later women, children, the elderly, and individuals long discriminated against and excluded from full political life in Sweden.

Social scientists linked to the dominant Swedish Social Democratic party played a role. At times they fashioned themselves as social engineers, eager to arrange the lives of the citizens, but they were not free to act as they pleased since they were subject to frequent electoral judgment. Thus, popular support for the nation’s peculiar social contract was from the start premised on the political leaders’ ability to grasp popular preferences. These included, prominently, a widespread belief in the importance of being independent of other people, of being autonomous and not subordinate or made indebted – whether that debt be economic, emotional or social. At the heart of this conviction is the idea that true love and friendship, indeed any authentic relationship, is built not on mutual dependence, but on equality, freedom of choice and autonomy. I have named this moral logic the Swedish theory of love.

The gap between the rhetoric of family values and the reality of poverty and solitude was clearly wide

To ordinary citizens, this social contract, as it over time evolved from vision to concrete reality, has proven very attractive. To explain why, let me first give two examples from my own life. The first one goes back to when I decided to apply to college in the US at the age of 19. While the academic requirements were easy enough to grasp, I was far less clear on the question of how I was to pay for tuition, room and board, which entailed considerable costs, even in the early 1970s. As it turns out, the financial office of the college that I had set my sights on – Pomona College in California – handed me two sets of forms to fill out. The first one concerned my own income and wealth – a simple matter of zeros and a signature – but the second one asked for my parents to submit similar information. This I found perplexing. In Sweden, the rules for financial aid in the form of grants and loans had recently been reformed so as to remove any consideration of parental or spousal income or wealth. The logic was that, as adults (if still young ones), students should not be beholden to parental control or be dependent on them in financial terms.

I raised this point to the financial aid officer in no uncertain terms. Since I was an adult, of what relevance was my parents’ financial situation? They explained that parents in the US were expected to contribute to the cost of higher education. I then noted the problem, as I saw it, that this could mean that parents could condition their support in a way that would restrict the freedom and autonomy of the student. What if, for example, I would like to major in history, with its questionable prospects for career and income, and my parents told me that they would support me only if I chose a major with greater promise, such as economics, pre-law or pre-med? As it were, this luckily did not matter much since my parents were as poor as I was. But the experience made me think about this difference in policy. What did it say about the relationship between state, family and individual?

Ten years later, I worked odd jobs in San Francisco: nighttime at a café, daytime for a nonprofit organisation called Meals on Wheels that provided meals for elderly people who had a hard time shopping for food and cooking at home. By this time, I was more familiar with the stress on ‘family values’ that was so important in the US and indeed in most parts of the world. So, I was puzzled to see how many of the elderly we served apparently suffered from the absence of both state support and familial care. The gap between the rhetoric of family values and the reality of poverty and solitude was clearly wide. Again, the difference between Sweden and most countries came to mind. As I later began to research the matter, I discovered that the laws in Sweden had been changed in the 1970s to transfer the legal and financial responsibility for the elderly from the grown children to the state.

Today, while social conservative critics at times bemoan this state of affairs, suggesting that dependence on the state breeds social isolation and loneliness, studies show that the elderly themselves appear to benefit. Not only do the elderly in Sweden and the other Nordic countries report higher degrees of happiness, but they are also more satisfied with their social networks. This research furthermore points to what is the essence of the Swedish theory of love, namely that social relations are voluntary, not ascribed – based not on duty but on free choice.

A third example is the logic underpinning the Swedish tax code. In 1971, joint taxation was eliminated in favour of strict individual taxation. The idea was that at a time when women began to flock to the labour market, joint taxation presented an obstacle in the form of a negative incentive. If a woman began to earn money, her income would be added to that of the husband, and in an era of progressive taxation that meant the woman’s income effectively would be subject to a higher tax. Add to this that before the 1970s there was no universal, tax-financed childcare yet in Sweden, meaning that such care – without which it would be impossible for both husband and wife to work – had to be paid for privately, a costly proposition.

The introduction of strict individual taxation – there was no option to select joint taxation – and, over time, universal daycare, created the conditions for women to enter the workforce en masse. This in turn gave them the economic independence without which talk of gender equality would only amount to rhetoric. These reforms, to which can be added the world’s first law criminalising the spanking of children, even at home, and the legalising of gender-neutral marriage, meant that the family became more and more of a voluntary society, rather than the old-fashioned traditional family characterised by patriarchal power relations. To be sure, these reforms, which one perceptive writer has referred to as a ‘bloodless revolution’, created opposition. One group called the Family Campaign collected some 60,000 signatures from irate housewives and religious conservatives to protest the new tax law. But, generally, support far exceeded opposition and the days of the Swedish housewife were indeed numbered.

The family is both the object and the collaborator of the welfare state

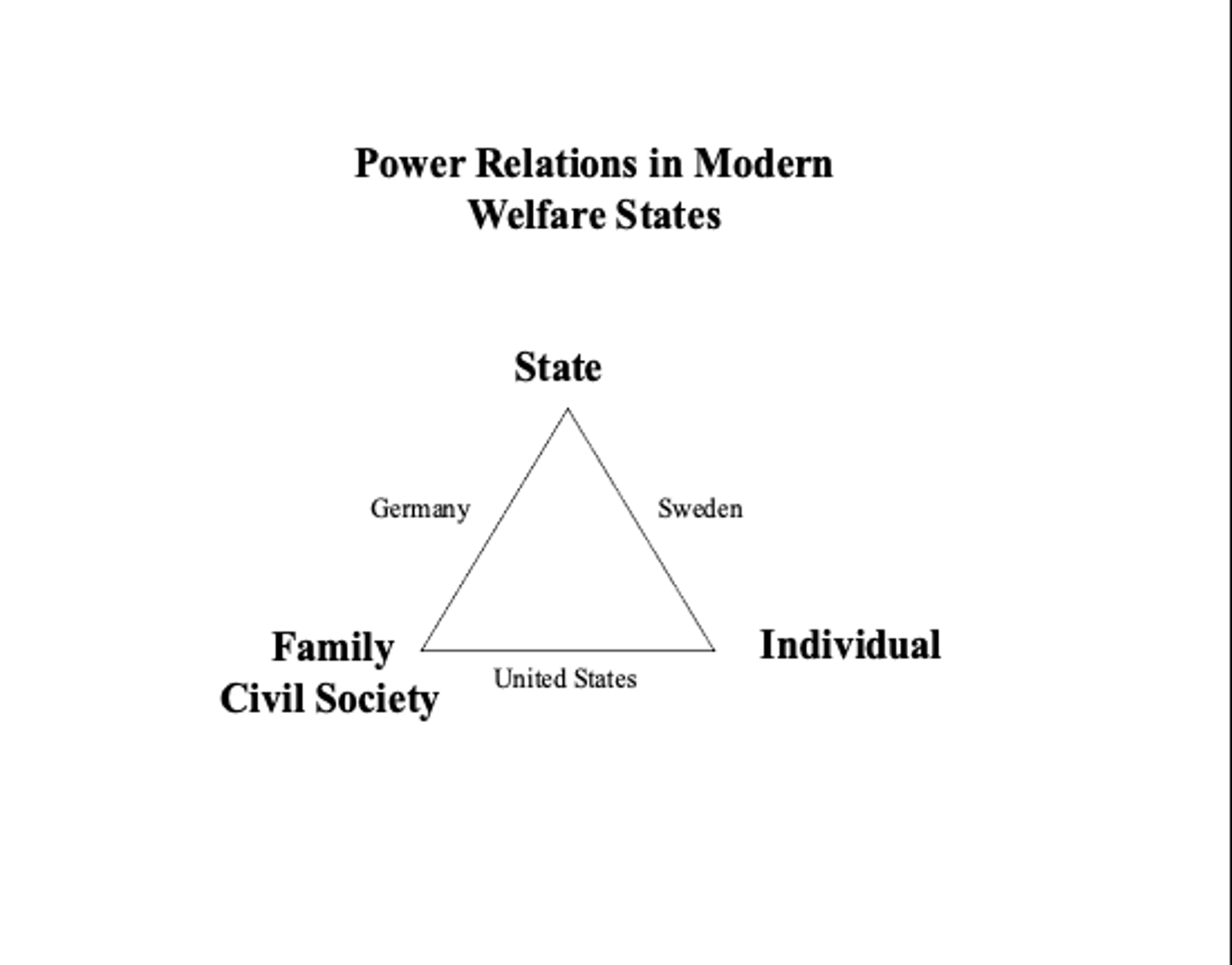

To illuminate the Swedish peculiarity in this regard, it helps to compare Sweden with Germany and the US, countries that in many ways are similar. All three are rich, vibrant, democratic market societies. Yet they sport radically different forms of social contracts, based on fundamentally different moral and political logics. To assist the comparison, the figure below is useful. It depicts a triangle drama, of sorts, involving the State, the Individual, and the Family/Civil Society, and how the dynamic works out in the three countries.

In Sweden, the dominant side is the one connecting the state and the individual. The state is viewed positively and one of the simplest expressions of a high-trust society, such as Sweden, is the willingness on the part of citizens to pay taxes. Individual rights are ‘positive’, taking the form of social rights and investment in individuals. In the US, on the other hand, the state is viewed with suspicion. The constitution and the political culture are characterised by a lack of trust in the state and a desire to protect the autonomy of the family and the Churches, as well as stipulating a bill of rights, ‘negative’ individual rights that seek to guard individual freedom from state power. Here the strong side is rather the one connecting the individual with family/civil society. In Germany, conversely, the key side is the one linking the state to family/civil society. The state is regarded as important in guaranteeing equal access to fundamental civic resources like education and healthcare, but with respect to actual implementation of social services, these are – whenever possible – to be delegated to the family and nonprofit organisations in civil society.

In Germany, welfare policy thus proceeds from the idea that the family is both the object and the collaborator of the welfare state. The state protects and supports the family as well as other institutions of civil society with the aim that each of these in turn should be able to provide for the welfare of individuals in the form of child- and eldercare, education and healthcare. Although the commitment of the public sector to its citizens’ social security is massive, its implementation is thought to be better carried out by actors in civil society, ranging from housewives to different kinds of charitable religious organisations. Strong bonds of dependence are regarded as natural, but there is also a consensus that the state bears a large ultimate social responsibility, as a final backstop. But the primary goal is that the family and the nonprofit organisations carry the central responsibility, according to the logic of subsidiarity – a principle, derived from Catholic social thought, that stresses the role of Church and family.

When the German state intervenes, it does so on the basis of needs testing – not according to a logic of the state providing universal social rights. In Germany, conditions of eligibility for state assistance often underscore the fact that the recipient is subordinate, dependent and incapable of coping on their own. However, because the moral norm does not hold up individual autonomy as a superior value, the degree of stigmatisation caused by dependency is reduced.

The US, as noted, is characterised by a deep-rooted antipathy towards state involvement in any aspect of the private sphere, whether in connection with the individual or the family. While the US welfare state is more comprehensive than both defenders and critics of the US model sometimes like to pretend, its point of departure is that the individual must stand on their own feet, within the parameters of the rules of the market, or rely on the goodwill and available resources of their family, religious/ethnic community or charity. The social security network exists primarily to help citizens who are unable to make their way in the market and lack the requisite support from their family or civil society. Both this faith in the individual’s right to find happiness and the powerful (and often religiously inflected) ideal of the family make it difficult to implement a more activist and universal welfare policy in the US.

In one important respect, Sweden resembles Germany with regard to its ambitions for welfare policy. Unlike in the US, Swedes and Germans more or less take for granted that the state is an actor in the promotion of citizens’ wellbeing. Yet Germany also differs radically in what it sees as the fundamental unit of society. In Sweden, resources and measures are, as we have discussed above, targeted at the individual citizen, without going via the family or nonprofit organisations. In this way, the state protects the individual from any risk of ending up in a relationship of dependency upon parents, spouses or charitable organisations. It also leads to the emancipated citizen becoming more mobile in the labour market, more easily governed through political measures, and more inclined to turn to the market to meet needs that would previously have been satisfied within the family. Social insurance, child benefit allowances, student grants and other forms of state redistribution take the form of unquestioned social rights, which accrue to individual citizens.

In some respects, there are similarities in how Sweden and the US view the individual. In both countries there is a strongly individualistic ethos. Both countries emphasise self-realisation and a modernist desire for change in preference to tradition and loyalty to a community. As regards gainful work for women, childcare outside the home, and single parents, both the US and Sweden rank high from an international perspective. The difference is that in Sweden the state is expected to support this striving for independence, and not only by offering a broad social security net. The Swedish social contract also places the obligation on the state to make resources available in a way that makes the individual independent of family, neighbours, employers and other collective networks.

Sweden’s exceptional status is evident in large-scale, quantitative research projects such as the World Values Study, noted above, which since the 1980s have produced a gigantic body of data on cultural differences, lifestyle variations, and different patterns of values within Europe and in the world at large. In measures of traditional values based on religion, family and nation versus emancipative values that emphasise self-realisation and individual autonomy, Sweden occupies an extreme position in the upper right corner of the ‘cultural map’.

As the Swedish sociologist of religion Thorleif Pettersson has noted in his analysis of the data, Swedes are characterised by having ‘the most atypical and divergent value profile of all’. In most areas of life, Swedes prioritise personal independence with respect to familial relations and traditional authority. From a European perspective, Sweden takes the pole position as regards citizens’ acceptance of divorce, view of men’s and women’s equal responsibility to provide income for the household economy, tolerance of other people’s sexual orientation, willingness to participate in political actions, and attitude towards the importance of personal responsibility. By contrast, Sweden comes near the bottom of the survey as regards the expectation that children should love and honour their parents, and the number of people who consider themselves religious.

Institutionalised nursing care is replacing the bonds between people that were once the basis for intimacy

Sweden also stands out in other comparative research into the values, practices and institutions associated with the family. From a global perspective, the Scandinavian countries have without exception all gone furthest in the process of individualisation. But even in this group Sweden is an outlier.

Defenders of the welfare state like to claim that the alliance of state and individual has delivered many advantages. All citizens in Sweden can use state welfare during difficult periods of their life without any stigma. Citizens feel safer knowing that there exists a fundamental degree of security, and they are accordingly more flexible and willing to change. Secure in the knowledge that there is a fine-meshed social security net, people feel free to gain an education, change job, get divorced and have children without ever becoming dependent upon family, employer or friends.

Yet Sweden’s strong emphasis upon individual autonomy has also been criticised. The state’s arrogation of traditional interpersonal commitments, it has been argued, is furthering the development of an increasingly cold and loveless society. Institutionalised nursing care is replacing the bonds between people that were once the basis for intimacy and closeness. High divorce rates, loneliness and poor mental health are often cited as negative consequences of the alliance between state and individual against the family.

Another recurrent criticism focuses less on the existential questions of individualism versus community and instead considers the matter from a power perspective. Autonomy in relation to other people has been purchased at a high price, the argument goes. Not only have the natural communities of civil society been undermined but citizens have subordinated themselves to the power of the state, a power that is not always exercised tenderly or considerately. Like the US and Germany, Sweden had a strong eugenics programme that led in the 1930s to forced sterilisations. One can draw a straight line from these awful measures – based on a law that was not repealed until 1976 – to the fairly weak rights that, even today, Swedes enjoy as individuals in relation to the state. Swedish political culture simply does not provide a constitutionally grounded division of power that allows for individual rights that can be claimed in a court of law. Sweden’s robust social rights are ultimately exercised not through civil contracts pursuable in courts of law but by professionals. For example, in the health sector, doctors and nurses are given broad responsibility to provide healthcare on equal terms to all citizens and residents. But when conflicts occur in cases of malpractice or decisions regarding prioritising, the individual patient consequently has little power to effectively question decisions.

However, the most salient challenge to the Swedish social contract has in recent years been the impact of rapid immigration resulting in a dramatic demographic shift. Today, more than 20 per cent of the population is foreign born. Furthermore, whereas the first waves of immigration during the 1940s to the 1970s involved labour migrants – as well as refugees who were effectively treated as labour migrants – more recent arrivals have been refugees. At the same time, the politics of integration has shifted from a stress on assimilation and integration through employment, towards a new ideology embracing ideals such as diversity and multiculturalism. The result has been a large number of immigrants who suffer from high rates of unemployment, linked to poor Swedish language skills, lack of education, and segregation in terms of both schools and housing.

Behind this shift lies a tension between two narratives regarding Swedish national identity. One, which has been the focus of this article, assumes a national social contract and citizens who work, pay taxes, and in this way earn rights. This involves a rather stern moral logic based on a conditional form of altruism rooted in the idea of reciprocity: the welfare state as a combined insurance company and investment bank; all adult citizens contributing through work, investing in the young, and ensuring social necessities of the elderly and unwell.

Modern Swedish society offers individuals maximal liberation with minimal moral consequences

The other logic – by which I call Sweden a ‘moral superpower’ – imagines a post-national world defined less by bounded, national solidarity among citizens than by a globalised community in the image of human rights, a vision that de facto challenges the national social contract. The welfare state becomes castigated as a form of exclusionary ‘welfare chauvinism’ that involves xenophobia and racism.

The unresolved tension between the logics of national community and a global human rights ethics has, during the past few decades, resulted in the rise of a party, the Sweden Democrats, that is openly anti-immigration, as well as in a more polarised political atmosphere that in itself threatens the social contract.

This said, one historical fact about Sweden’s welfare state remains: it represents a solution that is as unusual as it is successful in meeting the challenge of how society should balance individual striving for sovereignty with the reciprocal need of mitigating against social collapse and a ‘war of all against all’. Democratic, elective and deeply rooted in the nation’s history, modern Swedish society has been created on the basis of a social contract that offers individuals maximal liberation with minimal moral consequences.

The Swedish welfare state, and the social contract that it embodies, is also not simply a solution from above, imposed by fanatical social engineers. On the contrary, the impulse to break with close familial and other ties in civil society has been deeply anchored in popular practices and, moreover, has come to be regarded as an expression of solidarity rather than alienation.

Furthermore, while this social contract has been distinctly national, its fundamental principles are not ethnic, or race based. Rather the stress on individual autonomy and equal opportunity suggests a potential for the inclusion also of immigrants who often come from countries where they have been denied basic freedoms and opportunities. For this reason, the prospects for the Swedish social contract are still potentially good – assuming that integration becomes more successful, perhaps as the large flows of immigration are better controlled to allow time for inclusion, not least through work.