‘To me,’ wrote William Blake in 1799, ‘this world is all one continued vision of fancy or imagination.’ The imagination, he later added, ‘is not a state: it is the human existence itself.’ Blake, a painter as well as a poet, created images that acquire their power not only from a certain naive artistic technique, but because they are striving to transcend it – to convey a vision of the world beyond superficial appearances, which only imagination can reach.

For the Romantics, imagination was a divine quality. ‘The primary Imagination I hold to be the living Power and prime Agent of all human Perception,’ wrote Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1817. It was a powerful faculty that could be put to use, distinct from the mere ‘fancy’ of making up stuff – which all too often, is how imagination is conceived today.

Blake would have been unimpressed by modern scientific efforts to find imagination among the firing patterns of neurons, as if it was just another cognitive function of the brain, like motor control or smell perception. Likewise, he would have scorned the idea, favoured by some cognitive scientists, that imagination is a mere byproduct of more ‘important’ mental functions, evolved for other reasons – in the manner that the cognitive scientist Steven Pinker proposes that music is ‘auditory cheesecake’, piggybacking on basic skills required to process sound.

Compared with longstanding research about how we process music and sound, language and vision, efforts to comprehend the cognition and neuroscience of imagination are still in their infancy. Yet already there’s reason to suppose that imagination is far more than a quirky offshoot of our complicated minds, a kind of evolutionary bonus that keeps us entertained at night. A collection of neuroscientists, philosophers and linguists is converging on the notion that imagination, far from a kind of mental superfluity, sits at the heart of human cognition. It might be the very attribute at which our minds have evolved to excel, and which gives us such powerfully effective cognitive fluidity for navigating our world.

From an evolutionary perspective, the central puzzle of imagination is that it enables you to suppose, picture and describe not only things you won’t ever have experienced, but also things you never could experience, because they violate the laws that govern the world. You can probably imagine being the size of an ant, or walking on air, or living on the Moon. Take a moment: it’s not so hard, if you try.

But how can it possibly benefit us to have minds capable of such flights? Unlike vision or memory, after all, imagination doesn’t seem to be a cognitive attribute that’s widely distributed in the natural world. We’re probably safe to assume that dogs and chimps don’t imagine having wings or living in Renaissance Italy. Even in purely human terms, cognitive skills such as problem-solving, numeracy and social cooperation seem far more adaptively useful.

As for wisdom, let’s defer judgment until we’ve escaped (or not) the current path of self-destructive extinction

In the story science has taught us to tell about human evolution, the skills we have acquired serve as milestones. From around 2.3 million years ago, our ancestors in East and South Africa were Homo habilis, ‘handy man’ – so called because these hominins were able to do nifty things with their hands, in particular to make tools. Then around 2 million years ago, along came Homo erectus, distinguished by an ability to walk erect and upright. And finally, of course, Homo sapiens, the ‘wise’ or ‘knowing’ modern humans.

Yet are we sure these labels are the right ones? We’re not unique in using tools – apes, elephants, crows and parrots are among the other animals that can do so, and chimpanzees have considerable manual dexterity. Walking upright is no problem for gorillas. As for possessing wisdom and knowledge, perhaps we should defer judgment until we have escaped (or not) the current path of self-destructive extinction. Most of our other prized cognitive attributes – memory, empathy, foresight and planning, sociality, consciousness – are present in other species too.

The one mental capacity that might truly set us apart isn’t exactly a skill at all, but more a quality of mind. We should perhaps have called ourselves instead Homo imaginatus: it could be imagination that makes us human. The more we understand about the minds of other animals, and the more we try (and fail) to build machines that can ‘think’ like us, the clearer it becomes that imagination is a candidate for our most valuable and most distinctive attribute.

If imagination really is so important, you might expect it to be one of the best-studied of cognitive phenomena. On the contrary; understanding how the human organism summons up imagination has been given comparatively little attention, and is still largely a mystery. It’s just so much easier to study what goes on in the brain when we’re given a well-defined task – remember this sequence of numbers, see if you can spot the pattern in this image or solve this puzzle – than if you’re told to, well, just imagine.

When ‘imagination’ does surface in the neuroscientific literature, it’s often neutered by an overly narrow definition – an ability to form or recall mental visual images – rather than a description that embraces the true depth and range of human experience. There’s a difference between imagining a lion and a gryphon, for example. To be able to bring into the mind an image of a lion might have survival value, since it’s handy to mentally rehearse a scenario we’d best avoid. But where’s the value in imagining a creature with a lion’s body and a bird’s head? Why conjure up threats that have not only never existed, but could never exist?

Imagination blurs the boundary between mind and world, going well beyond daydreaming and reverie. When Theseus in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream says that imagination ‘bodies forth / The forms of things unknown’, he is voicing the Renaissance view that imagination produces real effects and manifestations: ‘One sees more devils than vast hell can hold.’ Here, Theseus echoes the 16th-century Swiss physician Paracelsus, who believed that demons such as incubi and succubae ‘are the outgrowths of an intense and lewd imagination of men or women’. From imagination alone, Paracelsus said, ‘many curious monsters of horrible shapes may come into existence.’ The problem with imagination is that it doesn’t know where to stop.

Perhaps the human mind overproduces possible futures in order to plan in the present

Even so, evolutionary psychologists might suppose that there’s some reason behind our ability to imagine the impossible. Since the laws of physics weren’t known to our species when our brains were evolving, should it surprise us that imagination wilfully breaks them? A mind that can conceive of possibilities beyond its own experience can prepare for the unexpected; better to overanticipate than to be surprised.

We already know that overproduction of possibilities, followed by pruning through experience, is a viable evolutionary strategy in other contexts. The immune system generates huge numbers of diverse antibodies, of which only one might actually fit with a given antigen and enable its removal or destruction. And the infant brain doesn’t gradually wire its neural connections as experiences accumulate; rather, it starts with a vast array of random connections that are then thinned out during brain development to leave what is useful for dealing with the world.

In the same way, perhaps the human mind overproduces possible futures in order to plan in the present. ‘The task of a mind,’ wrote the French poet Paul Valéry, ‘is to produce future.’ In his book Kinds of Minds (1996), the philosopher Daniel Dennett quotes the line, saying that the mind is a generator of expectations and predictions: it ‘mines the present for clues, which it refines with the help of the materials it has saved from the past, turning them into anticipations of the future.’

How do we construct such possible futures? The basic mental apparatus seems to be an internal representation of the world that can act as a ‘future simulator’. Our capacity for spatial cognition, for instance, lets us build a mental map of the world. We (and other mammals) have so-called ‘place cells’, neurons in the brain region called the hippocampus (which handles spatial memory) that are activated when we are in specific remembered locations. We also develop mental models of how objects and people behave: a kind of intuitive or ‘folk’ physics and psychology, such as the so-called theory of mind by which we attribute mental states and motivations to others. We populate and refine these cognitive networks from experience, creating memories of things we have encountered or observed.

Yet what we hold in mind are necessarily patchy, sketchy and wonky versions of ‘reality’ – good enough for most purposes, but full of gaps, false assumptions and recollections. What’s surprising is not the imperfections, but how little we notice them. That’s precisely because we are Homo imaginatus, the master fabulators. Craving narratives that help us make sense of the world, we unconsciously and effortlessly fill in or revise the details until the story works. In this sense, imagination is a normal part of what we do all the time.

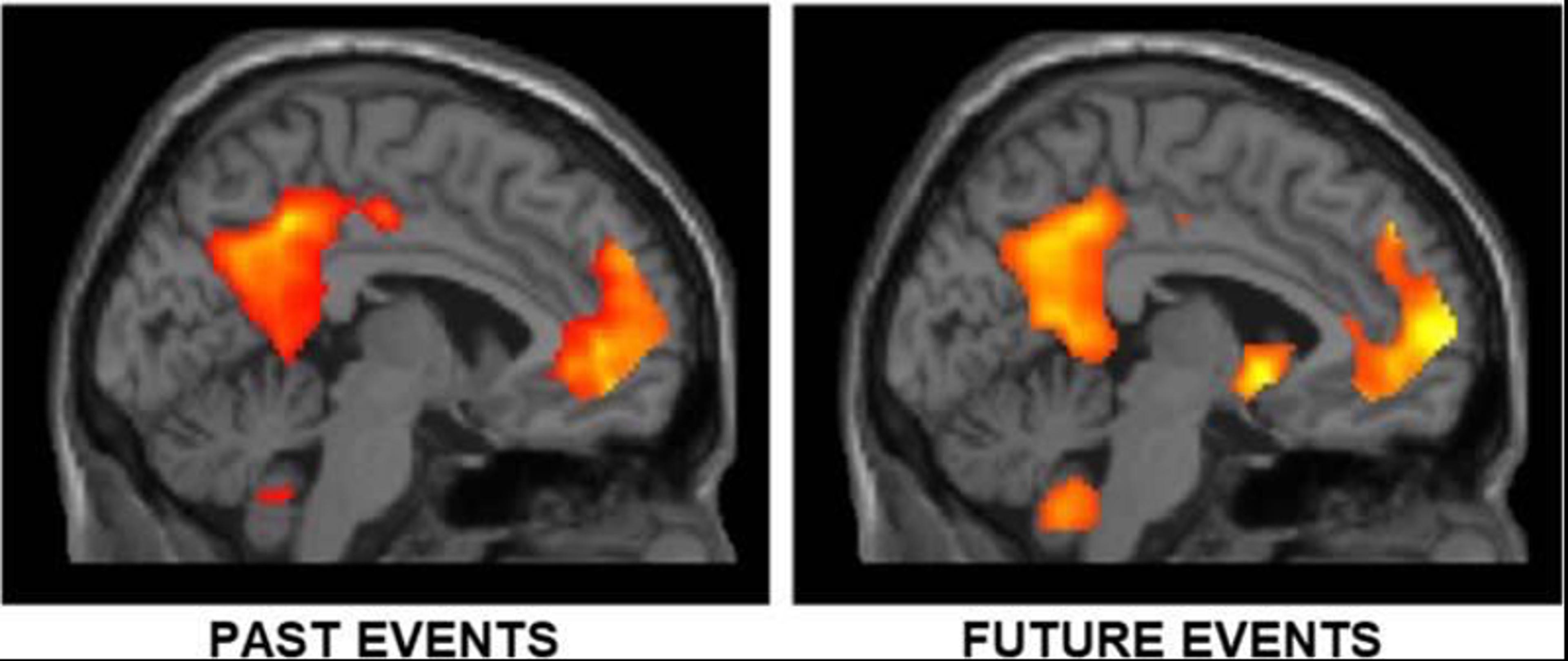

Moments of rumination, reflection and goal-free ‘thinking’ occupy much of our inner life. In these moments, our brains are in a default state that looks unfocused and dreamy, but in fact is highly active – planning supper, recalling an argument with our partner, humming a tune we heard last night. This way of thinking correlates with a well-defined pattern of activity in the brain, involving various parts of the cortex and the hippocampus. Known as the default mode network, it’s also engaged when we remember past events (episodic memory); when we imagine future ones; and when we think ahead, adopt another person’s perspective, or consider social scenarios.

The cognitive neuroscientist Donna Rose Addis of the University of Toronto has argued that imagination doesn’t just draw on resources that overlap with episodic memory; they are, she says, ‘fundamentally the same process’. Impairments of the ability to recall episodic memories seem to be accompanied by an inability to imagine the future, she says – and both abilities emerge around the same time in childhood.

In this view, imagined and remembered events both arise by the brain doing the same thing: what Addis calls ‘the mental rendering of experience’. Imagination and memory use a cognitive network for ‘simulation’ that turns the raw ingredients of sensory experience into a kind of internal movie, filled not just with sound and action but with emotional responses, interpretation and evaluation. Not only is that happening when we think about yesterday or tomorrow, says Addis – it’s what we’re doing right now as we experience the present. This simply is the world of the mind. The imaginative capacity, she says, is the key to the fluidity with which we turn threads of experience into a tapestry.

In some sense, we are all that poet, all the time

Here Addis expands on the notion proposed by her sometime collaborator, the psychologist Thomas Suddendorf at the University of Queensland: imagination is a kind of mental time-travel. As he put it in 1997, imagination is ‘the mental reconstruction of personal events from the past … and of possible events in the future.’ Suddendorf and his colleague Michael Corballis of the University of Auckland in New Zealand argued that mental time travel might be a uniquely human trait, although there is still debate about whether other animals really do live in a kind of perpetual present. The capacity draws on a range of other sophisticated cognitive functions to create a kind of mental theatre of possibility.

This ability could seem curiously asymmetrical – the past actually happened, while the future is just conjecture, right? Well, not really. Much as we might like to think we remember ‘what happened’, a vast body of evidence shows that our memories are an intimate blend of fact and fantasy. We construct a narrative out of the imperfect, disjointed materials that the world supplies and the mind records. We’ve all had false memories, some of them so richly detailed and convincing that we can’t quite believe they didn’t happen. As the philosophers of mind Kourken Michaelian and Denis Perrin of the Université Grenoble Alpes in France have put it, ‘to remember simply is to imagine the past’. Our grip on reality depends then not on distinguishing between the real and the imagined, but between two types of imagination – one interwoven with reality, the other more distant from it. Failure to do so is a common feature of many types of mental illness, some of which are known to be associated with dysfunctions of the brain’s default mode network.

Addis now views the imaginative capacity as something broader than the purely temporal. In our mind’s eye, we can project ourselves ‘anywhere in imaginary spacetime’ – into medieval France, or Middle Earth, or The Matrix. In that inner theatre, any performance can take place. As Theseus said: ‘Lovers and madmen have such seething brains, / Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend / More than cool reason ever comprehends.’

Addis argues that the brain’s simulation system can produce such fantasies from its facility at association: at weaving together the various elements of experience, such as events, concepts and feelings. It’s such associative cognition – one set of neurons summoning the contents of another – that allows us to put names to faces and words to objects, or to experience the Proustian evocation of the past from a single sensory trigger such as smell. This way, we can produce a coherent and rich experience from only partial information, filling the gaps so effortlessly that we don’t even know we’re doing it. This association is surely at work when a novelist gives attributes and appearances to characters who never existed, by drawing on the brain’s store of memories and beliefs (‘That character has to be called Colin; he wears tanktops and spectacles’). In these ways, the poet ‘gives to airy nothing / A local habitation and a name.’ In some sense, we are all that poet, all the time.

If Addis is correct, it would be quite wrong to suppose that the artistic imagination is just an evolutionary overdevelopment of an ability to plan how we’ll get tomorrow’s meal. On the contrary, the imaginative dimensions of the arts could be the paradigmatic expression of our skills at prediction and anticipation. The literary scholar Brian Boyd of the University of Auckland thinks this is where our predilection for inventing stories comes from. Specifically, he thinks they serve to flex the muscles of our social cognition.

Some evolutionary biologists believe that sociality is the key to the evolution of human minds. As our ancestors began to live and work in groups, they needed to be able to anticipate the responses of others – to empathise, persuade, understand and perhaps even to manipulate. ‘Our minds are particularly shaped for understanding social events,’ says Boyd. The ability to process social information has been proposed by the psychologists Elizabeth Spelke and Katherine Kinzler at Harvard University as one of the ‘core systems’ of human cognition.

Boyd thinks that stories are a training ground for that network. In his book On the Origin of Stories (2009), he argues that fictional storytelling is thus not merely a byproduct of our genes but an adaptive trait. ‘Narrative, especially fiction – story as make-believe, as play – saturates and dominates literature, because it engages the social mind,’ he wrote in 2013. As the critical theorist Walter Benjamin put it, the fairy tale is ‘the first tutor of mankind’.

‘We become engrossed in stories through our predisposition and ability to track other agents, and our readiness to share their perspective in pursuing their goals,’ continues Boyd, ‘so that their aims become ours.’ While we’re under the story’s spell, what happens to the imaginary characters can seem more real for us than the world we inhabit.

Through language, a listener can put together the experience of what is described

Imagination is valuable here because it creates a safe space for learning. If instead we wait to learn from actual lived experience, we risk making costly mistakes. Imagination – whether literary, musical, visual, even scientific – supplies material for rehearsing the brain’s inexorable search for pattern and meaning. That’s why our stories don’t have to respect laws of nature: they needn’t just ponderously rehearse possible real futures. Rather, they’re often at their most valuable when they are liberating from the shackles of reality, literally mind-expanding in their capacity to instil neural connections. In the fantasies of Italo Calvino and Jorge Luis Borges, we can find tools for thinking with.

If imagination is then our USP, it might also catalyse a trait that seems unique to humans: language. While many organisms, including even bacteria and plants, communicate with one another, none can do so with the versatility, sophistication and open-endedness of human language, what’s often called our most important technology. ‘First we invented language,’ says the linguist Daniel Dor of Tel Aviv University. ‘Then language changed us.’

Language has long been regarded primarily as a tool for clearer, more precise communication than nonhuman animals’ smaller repertoire of vocalisations or gestures allows. But in Dor’s view, precision isn’t its real function at all; rather, it’s primarily about the ‘instruction of the imagination’. Language, he argues, ‘must have been the single most important determinant of the emergence of human imagination as we know it.’

Dor cites Ludwig Wittgenstein’s remark in Philosophical Investigations: ‘Uttering a word is like striking a note on the keyboard of the imagination.’ We use words, he says, ‘to communicate directly with our interlocutors’ imaginations.’ Through language, we supply the implements by which a listener can put together the experience of what is described. It’s a way of passing actual experiences between us, and thereby ‘opens a venue for human sociality that would otherwise remain closed.’

What this means is that language is ‘basically for telling stories’, in the words of the psychologist Merlin Donald at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio. Of course, we use it for a lot of other things too: for greetings, requests, advice, warning and argument. But even there, language is often deeply imprinted with narrative and metaphor: it’s not a mere labelling with sound, but refers to things beyond the immediate object. To imagine etymologically implies to form a picture, image or copy – but also carries the connotation that this is a private, internal activity. The Latin root imaginari carries the sense that oneself is a part of the picture. The word itself tells a story in which we inhabit a possible world.

Thanks to language, imagination doesn’t just involve fantasies of tonight’s meal, or worries about where it will come from. It conjures up grotesque monsters, galactic empires, fairy stories. Dor believes that this fecundity is unique to humans. He believes other animals can mentally time-travel, but sees no sign that they create unconstrained narratives. ‘It is this unique [human] capacity that makes language so important in the story,’ he adds.

Nor is it surprising that our visions are often so bold and bizarre – that we have a propensity to see ‘more devils than vast hell can hold’. For if Boyd is right that stories do vital cultural work by rehearsing social dilemmas, contemplating fears and anxieties, and indulging forbidden desires, it would make sense for them to take extreme forms. The more vivid and exaggerated the characters, the more engaging and memorable. It would explain too why so many stories involve high-stakes situations, such as love and death – for those are the situations in which errors of judgment matter more. Sure, Jane Austen might offer refined social instruction, but there are roles for Dracula and Godzilla too.

Imagination might be the very epitome of how our minds work: not as a series of isolated modules, but as an integrated network in which higher-order capacities arise from lower-order ones. It’s not so much a cognitive ability as the focus of and rationale for human cognition itself: a nexus of capacities we can find in more fragmentary form in other animals. Just as many species have aspects of musicality (such as pitch discrimination or rhythmic entrainment) but only humans have genuine music, so many species have what we might call imaginality. Yet we alone might possess imagination.

People aren’t born being innately ‘good at imagination’, as if it’s a single thing for which you need the right configuration of grey matter. It is a multidimensional attribute, and we all possess the potential for it. Some people are good at visualisation, some at association, some at rich world-building or social empathy. And like any mental skill (such as musicianship), imagination can be developed and nurtured, as well as inhibited and obstructed by poor education.

As we come to better understand what the brain is doing when it imagines – and why it is such a good imagining device – we might start to break down the preconceptions and prejudices that surround imagination. We might stop insisting that it is the privilege of an elite – the poets, dreamers and visionaries – that the rest of us can only hope to consume what they produce. Imagination is the essence of humankind. It’s what our brains do, and in large part it may be what they are for.

This Essay was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon+Psyche from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon+Psyche are not involved in editorial decision-making.